Adventures in DVD #3: “A Single Man”

Colin Firth jumped into a lake. It was the mid-1990s and the Englishman made the gnarly leap fully clothed, ensuring that his shirt would be clinging to his chest like stubborn cleaver post-dip, when he unexpectedly bumped into Elizabeth Bennet, their interaction producing enough sexual tension to light up a chandelier. The script for BBC’s adaptation for Pride and Prejudice had actually required Firth’s Mr. Darcy to take the plunge appropriately naked. Why the alteration was made isn’t totally clear, but such iconic pop culture moments aren’t always meticulously planned, they can be bolts of genius that materialize out of air and dust. What is clear is that from the moment that episode aired, Firth’s career was set on its path. The lake scene is often named one of the greatest British TV moments of all time.

The spectre of Darcy defined Firth the actor. He made all sorts of movies through the 2000s, but the commercially successful ones tended to be in the same vein. (Let’s call this the Meg Ryan problem, when an actor gets tagged as one-note because their attempts to break free of typecasting don’t find a big audience). That Firth essentially played the same role across a couple of Bridget Jones’s Diary movies was veiled so thinly that the character was named Mark Darcy. When Richard Curtis made Love, Actually—less an original movie and more a compilation of beats taken from popular romantic comedies—there was Firth, jumping into another lake, once again fully clothed. The title of a Times profile on Firth published in 2007, two years before the release of A Single Man—the film we are here to talk about today—was titled ‘Darcy Simply Won’t Die.’

A Single Man opens with a dream sequence and Firth once more submerged in water. But this time, his character is desperate, panicked, and unable to surface. Bathing in the conceptual depths of water as an allegory for distress and depression isn’t exactly original, but considering Firth’s association with life’s sweet elixir, it’s a striking way to get things started.

Frothier awards season favorite The King’s Speech was released a year after A Single Man. Casting Firth as King George VI, it would prove to be the final, defining skirmish in his war against his rom-com image—I mean, he collected the Oscar for Best Actor. But A Single Man remains his greatest work, the firebombing of all that came before, when everything you knew instantly disappeared. He was never quite as good again.

Set in Los Angeles, 1962, A Single Man follows a day in the life—or perhaps a life in the day—of George Falconer (Firth), a middle-aged British educator, single only because of the death of his partner Jim (Matthew Goode) in a car crash eight months prior. At the end of this languid day, George intends to relieve his grief by taking his own life.

“Just get through the goddamned day,” says George via a quiet internal monologue as he goes through his normal AM routine, assembling his perfectly primped self, capturing the absurdity of how every morning we put on our masks to present to the world. “Bit melodramatic, perhaps, but then again, my heart has been broken. Feel as if I’m drowning, sinking, can’t breathe.”

His planned final day on this planet sees George lecture on Aldous Huxley to a classroom full of totally uninterested students, bar Kenny (Nicholas Hoult), who may be more interested in Mr. Falconer than Mr. Huxley. He turns down the approach of flighty young Spaniard Carlos (obvious fashion model Jon Kortajarena) outside of a liquor store to instead share a cigarette in a car park in front of the smoggy L.A. sun. When George does attempt to take his own life, it’s almost farcical as he fumbles around to find the right direction to point the gun at his head. The indignity of it all for a man whose dignity provides an impenetrable outer shell. Instead, he keeps an appointment to knock back cocktails with well-off friend Charley (Julianne Moore). They drunkenly dance to Etta James’s version of “Stormy Weather” and “Green Onions” by Booker T and the MGs and Charley wonders what her life would have been if their romantic interactions in youth had been played out in full—not the first time she’s had such thoughts, I suspect.

How George got to this desperate point is told through flashbacks depicting his relationship with Jim. We see early on how George received the news of Jim’s death via an unexpected phone call from Jim’s cousin, Harold Ackerly (hey kids, it’s an uncredited voice cameo from Jon Hamm). The formality of their conversation is stiflingly uncomfortable given the gravity of the news: the pair refer to each other as Mr. Falconer and Mr. Ackerly; George politely thanks him for the call like he’d just phoned to confirm an appointment, despite being told he’s not welcome to a funeral service of a man he’s been in a relationship for 16 years (“Family only” is the lame excuse). The unnaturally stiff conversation reminds me of how cruel artificial social norms can be.

Adapted from the 1964 novel by Christopher Isherwood, one of a number of gay artists who absconded from Britain for the palm trees of Cali in the middle of the 20th century, A Single Man captures the brutal difficulties often endured by gay people after their spouses died. Domestic partnerships were not available to gay couples in California until 1999, with gay marriage coming a few years after that. Barriers, both legal and societal, meant families could easily ostracize them from their partner’s funerals and from all memory of that person. The way George ghosts through the world feels a symptom of not just missing Jim, but that he’s entirely alone in his grief, unable to partake in any of the arrangements that might provide some support and comfort, not acknowledged as the love of Jim’s life. He’s alone with the not overly compassionate Charley, and the scattered recollections of Jim that come to him throughout the film.

I’ve gotten this far without mentioning that the movie is directed by Tom Ford, a fashion designer so admired that Jay-Z was rapping about him during the height of Jigga’s high-end brand obsession phase. I won’t pretend to be an expert on Ford, but I hear he was a pivotal figure at Gucci in the 1990s. Anyway, Ford’s vision for A Single Man is stunningly sleek, the very best of 1960s minimalism and modernism. With Dan Bishop’s production design and Eduard Grau’s cinematography, Ford captures a romantically idealized vision of the period, life presented as sharp and stylish as an expensive timepiece. It’s shot with clean lines; a vision of the 1960s shared at the time by Mad Men, but even that show didn’t have Ford’s visual instinct. When he feels the need to, the director plays with the color filter, allowing brightness to break through the movie’s muted tones in front of our eyes, like sunbeams through clouds. The score, written by Abel Korzeniowski and Shigeru Umebayashi, is full of lush classical music, all sad string instruments, that match the sharpness of the dialogue. Cold War dispatches come through background radios, adding an era-specific ripple.

There were some accusations that Ford over-stylized the movie, but that’s nonsense. Cinema is allowed to be beautiful. If you can keep the internal logic of the universe while making every shot look like a photography print, then do it. Muse on the beauty, drink it in. Ford is too talented to go full Barney Gumble. “Sometimes awful things have their own kind of beauty,” says Carlos, the Spaniard, capturing the duality of the sad themes and pleasing aesthetics.

This is an assured debut from Ford. Some first-time directors overstuff their movies with too many ideas, but guided by the source material, A Single Man is tight in its intentions.

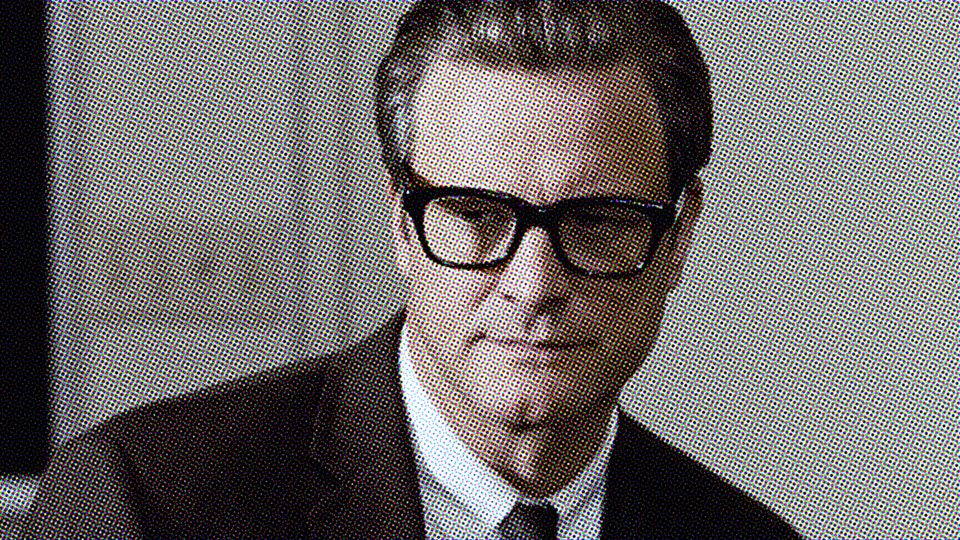

Then there’s Firth, walking through the film in full confidence that Ford will make something beautiful. With his perfect suit, polished shoes, crisp white shirt with no creases, and elegant spectacles, the immaculately crafted actor is pushed out into the world looking tightly wound to an inch of his life. Emotions come through as facial twitches and nothing more; dialogue recited with almost spider web softness. The subtleties of his performance require full attention, which is fine because who could possibly look away?

Adventures in DVD is my series on every great movie of the 2000s. If you’d like access to all past and future posts, and to support what I do here, please consider subscribing.