DEAN MAGAZINE Meets Eoin Ó Broin: His Life in Music

You know Eoin Ó Broin as a TD for Dublin Mid-West and Sinn Féin’s spokesman on housing. That department is a particularly tough ministerial draw these days with Ó Broin in opposition. To many, he’s the spearhead that will tear through the wretched policies that have seen Ireland corkscrew further and further into a housing crisis in recent years. I’ve even seen opposition skeptics concede that Eoin “knows his stuff.” So there you go.

There’s plenty of material out there on Ó Broin’s housing ideology—I mean, he wrote the book on the subject. So we leave all that to one side to speak on a completely different topic: music. It’s a passion that has spanned the 49-year-old’s life and, when he was younger, his ambition. In a way, Ó Broin’s youth is the most common story in rock, featuring kids with cheap instruments and big dreams. It starts in school halls and suburban homes, and continues in the grottiest, most glorious music venues of 1980s Dublin, almost all now shuttered.

“For me music has always been my most important cultural form in my life,” Ó Broin tells me over Zoom. “I take interest every so often in architecture or painting or theatre at different points. Music has been the constant.”

Born in 1972, Ó Broin grew up in Cabinteely. The earliest influencers on his listening habits were entirely typical: he checked out the music his brother and some of the older kids from the area were into. Luckily, their taste was unimpeachable. At around age 12, Eoin landed a copy of The Jam’s Dig the New Breed, a compilation of live performances. Later, he came across a teenager living in the estate who was selling off his record collection. Eoin picked up Inflammable Material by Stiff Little Fingers, an album, he says, “memorized” him.

“A lot of older brothers that were looking for money to take their girlfriends out, they were quite happy to flog some of it to their younger brothers and their younger brothers’ friends,” says Ó Broin. “I built a very small but nice collection over the space of a year or so of second hand punk albums.”

As he got more seriously connected with music in his mid-to-late teens, Eoin started excavating Dublin’s record stores. There was Freebird Records, located on Grafton Street at the time, and Comet Records, then on Chatham Street. (Both stores moved around in years since, such is the plight of the music shop. Freebird still exists as a component of The Secret Book and Record Store on Wicklow Street, while Comet shuttered its striking Temple Bar store in 2011.) Young Eoin’s collection grew to include the daring of sounds of bands like Birmingham’s GBH, left-wing punk group The Redskins, and compilations like Punk and Disorderly.

“Of course, there were other bands that were there that were more mainstream in terms of availability like The Specials and The Beat and the two-tone stuff,” he explains. “The good ends of mod, ska, and punk, that was easy to come by. But that wasn’t new music at that stage. A lot of that stuff was from the ‘70s or early ‘80s. So getting your hands on new music was much more difficult, but that wasn’t something many of us knew about until a later stage. We were just happy dealing with the stuff that had already been out for a decade or so.”

Then there was his interest in rockabilly music—Eddie Cochran and the like. Through the portal of rockabilly, he developed a taste for what would become the passion of his youth: psychobilly.

For the uninitiated, psychobilly is a subgenre that infused rockabilly—a strand of 1950s rock‘n’roll music from the American South—with a more belligerent punk aesthetic. Some of Ó Broin’s favorite psychobilly artists of the day included King Kurt, Guana Batz, and The Tall Boys. But he also fully bought into the culture. Eoin splashed bleach on his denims, recruited more artistic friends to paint wild designs on the back of his jackets, and grew out a 12-inch fringe, with a number one blade cut across the rest of his head.

“At the weekends this would have been quiffed up to full psychobilly quiff,” he says. “It would take a full bottle of cheap and toxic hairspray to get all of that going. That was very much part of it.”

Like every generation of skeezers and weirdos since, the city centre was where Dublin youth culture gravitated. The predominant subculture at the time was the soft goths. They dug The Cure, German industrial music, stuff like that. On Saturdays, HMV on Grafton Street was where the goths congregated, decorated in the deepest shades of black the human eye can process. Then you had the psychobillies. “There was a small number of us who were more like characters from a 1950s B movie,” says Ó Broin with a smile.

The premium psychobilly band in Dublin at the time were Shark Bait. Just about gig-going age, Eoin would rock up to the Belvedere Hotel to see the outfit perform. Inevitably, the shows became rough affairs. Funnily enough, Shark Bait would disband when leading man Dave Finnegan landed a role in The Commitments as the batshit bouncer who becomes the band’s drummer, this time turning a fictional group’s gigs into mini riots.

Ó Broin was also a massive fan of Billy Bragg, who he saw a few times at The Olympia. Years later, English singer-songwriter Leon Rosselson would grant Ó Broin permission to print the lyrics to “The World Turned Upside Down” in his book, Home. Eoin had first heard Bragg perform the song, and its message that land should belong to the people embedded itself in his brain.

Meanwhile, Eoin was finding himself as a musician. He’d developed an interest in playing as a boy at Willow Park Junior School, where a music class delivered the novel lesson of watching a Tom and Jerry cartoon and highlighting the score. Eoin joined the brass and wind band, playing the euphonium and the baritone horn. Crucially, the school had a double bass in its music room and Eoin would tinker with the mighty six-foot instrument. He later bought a second hand bass guitar, his favoured weapon moving forward.

It was during a summer break from school that Eoin joined his first band, coming together with two friends from different schools: Dave Cleary, these days a visual artist, and a guitarist named Darragh. The sum of their collaboration was one concert, where the group played three songs: “Light My Fire” (Dave being a Doors fan), Eddie Cochran’s “Come on Everybody,” and the third O Broin can’t remember now.

“We were brutal!” he admits. “But that got me into it.”

The chief outlet of Ó Broin’s career as a musician proved to be The Foremen. The group was founded in 1986 with Eoin on bass, Simon Crosbie on rhythm guitar, John McCabb on lead guitar, and Gavin Buckley on drums. The Foremen became a prominent support act for the mainstream, once opening for the Tom Dunne-fronted pop-rock band Something Happens at the SFX Hall. I once read that The Foremen supported Rory Gallagher’s last ever gig, but Ó Broin can’t confirm that with any certainty. He does remember feeling like a star when flown to an Irish rock and blues festival at the Mean Fiddler in London to play on the same bill as Gallagher.

“We got up on stage to do the Rory Gallagher gig and it was just filled with full-on bikers. A serious, serious rocker gig. And these were old bikers, these were guys in their 50s and 60s. So we got up, we did our set, we lashed it out as hard and fast as we could. We went out to the bar and I just remember these big, big rockers—classic Hell’s Angels guys—coming up to us and saying. ‘Your music’s shit! But god, you’ve got balls playing an audience like this. What drinks can we buy you?’”

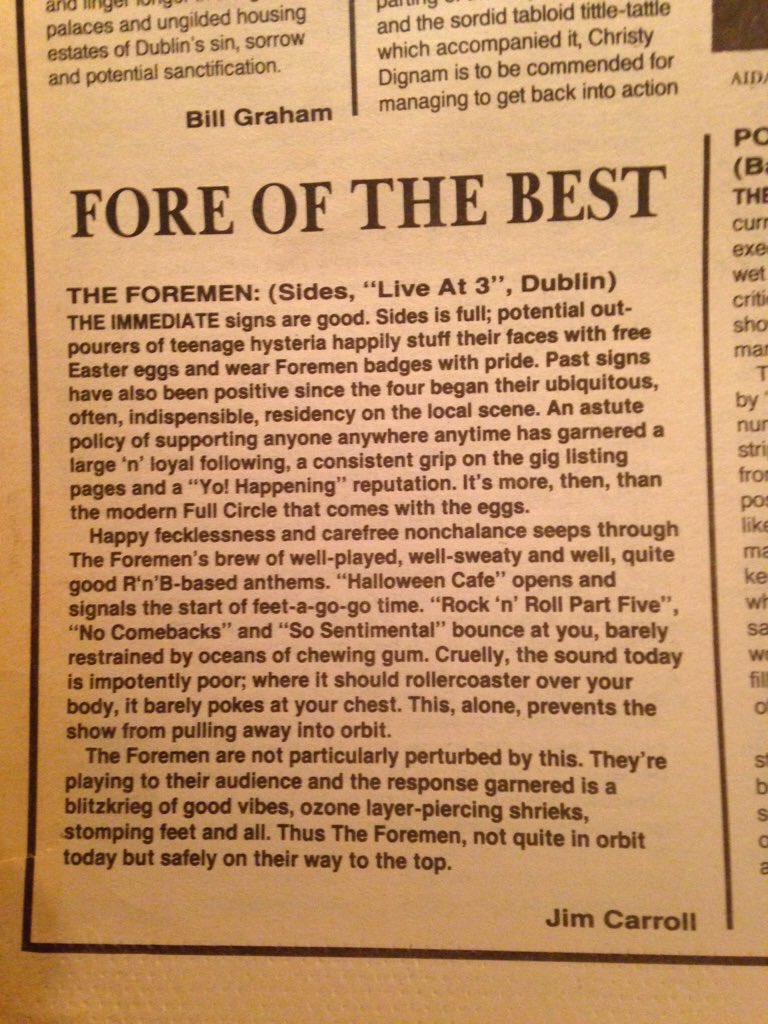

The Foremen also scored their own residency in the Gratton Hotel. Between that, the support shows and more, by 1988 they were playing a gig a week. This included the now-antiquated idea of no-alcohol shows for kids in the afternoon at McGonagles on St. Anne Street. Jim Carroll gave them a nice write-up in Hot Press.

“We would screen the Pope’s visit to Ireland or, alternatively, the old Batman movie, filled with dry ice,” describes Ó Broin. “We had a loyal teenage fans. Our peer group used to come to all the gigs. The place would be packed to the rafters.”

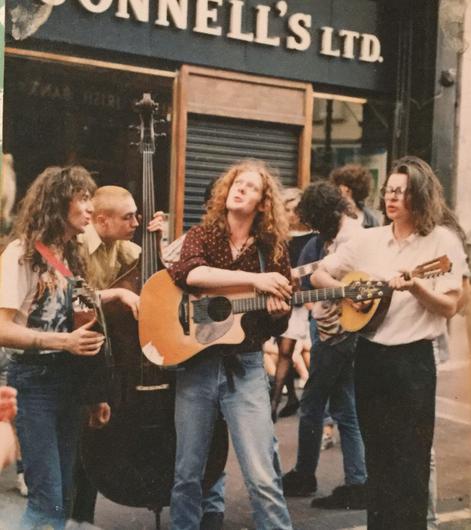

Additionally, the band were prominent buskers, running in a peer group that included musicians Mic Christopher, Glen Hansard, Mark Dignam, The Cheila Brothers, and Dave Odlum. For street performances, Ó Broin handily had a double bass he could perform on unplugged. For up to five hours they’d play on Grafton Street in the summer with up to 200 people watching on. Then they’d gather up all the coins and go off and do their thing.

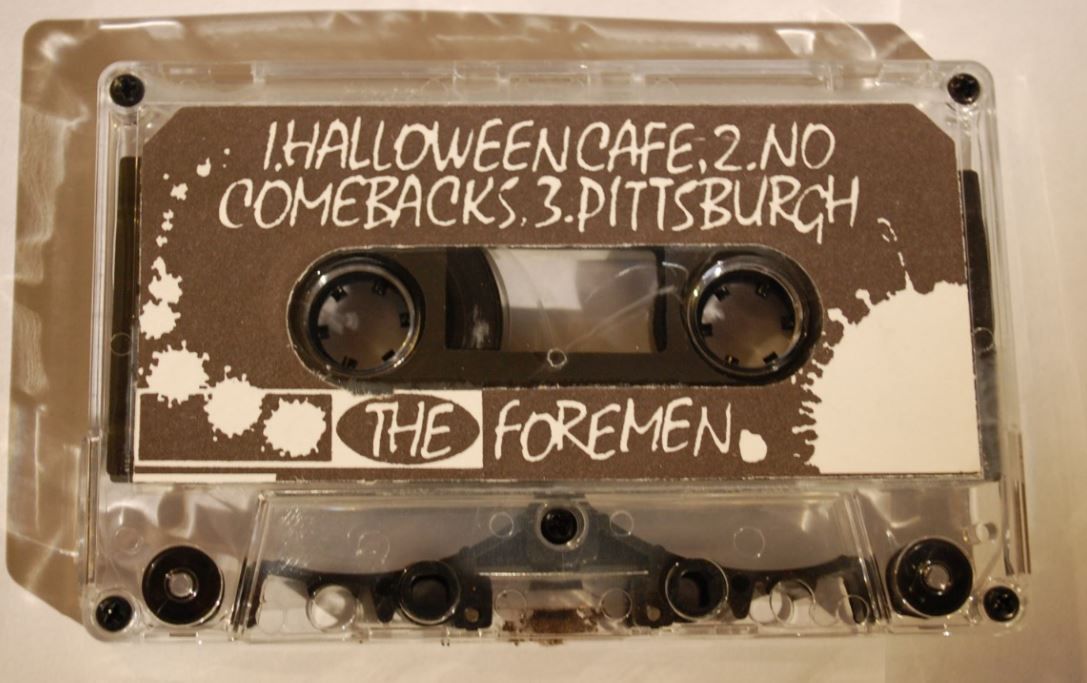

The sum of The Foremen’s recording career was a demo tape laid down in Temple Bar Studios and released in 1988, thankfully preserved by website The Fanning Sessions. O Broin’s songwriting contribution was “Pittsburgh,” a distinctly rockabilly-inspired tune that sees him sing about a guy who drinks too much tequila.

“They were all three-chord, crappy-lyric [songs],” he says. “Because I was in the psychobilly buzz, the more American cities and towns I could get named in a single song, the cooler it apparently sounded.”

The band circled the tape around various A&R men in London without hearing anything back. But Crosbie’s dad started talking to Denis Desmond, future influential music promoter. Desmond made a proposition: he would fund the band for three years as they sought a record deal. At the same time, Hansard had leveraged his own demo into a contract with Island to form a band that would become The Frames. Requiring a bass player, he approached Ó Broin, his busking buddy.

“In my great wisdom, having been given two pathways to a professional career as a musician, I turned them both down,” he says.

That was it. The Foremen fizzled out, and Ó Broin absconded to London. In a new city, he focused on education, studying for his A Levels and, later, attending college. Add in work and it left little time for playing music or even going to gigs, but he did buy a lot of records as more stuff was available in the English capital. Sebadoh and Fugazi became new favourites. He admits to having an antipathy to electronic music of the day, something he’s thankfully grown out of.

“Rave culture had just kicked off. There was still that tension between those of us who liked so-called real music with guitars and sweat and blisters on your fingers, and the emerging electronic music scene. I wasn’t in any way part of that and that was happening around the big clubs and off-site raves. For me, it was all still guitar music.”

The only exception to that was when Ó Broin spent a period squatting in North London. “The lads I was squatting with, they would have been a little older than me, and they would have been that generation that moved to London in the squats and got very into hardcore, but also that early, ambient electronica. Partly because they were taking a lot of acid half the time, and an awful lot of speed the other half.”

Still, he cites 1991 album The Orb’s Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld by progressive electronic group The Orb as a favourite. “It was only when I moved to Belfast in the mid-90s that I started listening to a lot of that stuff, particularly a lot of the retro electronica, like Solvent, like Plaid. I kind of go back to those analogue sounds and the general analogue revival.”

The rest of Ó Broin’s biography is well told: there was that period in Belfast, he joined Sinn Féin, wrote various books, and put himself forward for elections, first winning a seat in the Dáil in 2016. These days his listening habits often revolve around 20th and 21st century composers, with John Cage and Phillip Glass two of his favourites. “For me, it is the ultimate experimentation in musical form, way way beyond anything in say rock or folk music,” he declares. “Those crossovers between ambient, electronica and contemporary classical composition for me are the really exciting things.”

Still, he holds an interest in Dublin artists relevant to political portfolio. The likes of Gemma Dunleavy, Mango X Mathman, and Fynch have used their music to protest the old town slowly transforming into a soulless dystopia, more a commercial district than a city, fewer residents within its boundaries, no culture to speak of.

“First of all, I really like the lyrics. I really like the fact that they’re talking about very specific sets of struggles for young Dublin people living here now. Because of what I do in my political life, that speaks to me. But I also like the music. What I like about Fynch is there’s enough electronic in there to keep me interested. Some of the spoken word on that Mango X Mathman album [Casual Work, from 2019], like that opening spoken word track, are just really powerful.”

Kojaque is another new favorite: “Some of the grittier tracks on the new album [Town’s Dead] are really powerful stuff. But also there’s an anger in some of those tracks and it’s really explicit. It’s an anger about being forced out of the city that he wants to make music in and wants to live in culturally. For me, that’s when the stuff gets interesting, when there’s a mixture of something that’s authentic in the content.”

That his interest is piqued by new music with overt social messages just reasserts his belief in music’s power to inspire political movements. In fact, hindsight makes him wonder if an appreciation for rebellious music by nonconformist innovators planted seeds in his subconscious.

“People ask me, ‘When did you first get involved in politics?’ It’s funny because these things happen sometimes by osmosis or gradually to the point you don’t realise it,” he says. “When more overt politics became accessible, when I was in college or involved in the trade union in my work place in London, the stuff I was hearing, I’d been listening to that for a bunch of years [through music]. You don’t make those conscious connections, but that’s definitely the case. But also, even in a more general sense, one of the things that attracted me to the types of music I’ve always listened to is it’s always been music outside of the mainstream, it’s always been music that’s tried to push the boundaries of its particular genre.”

He continues, “There’s got to be a connection between that and where I gravitated to politically. Again, those political movements, political parties, ideologies that were outside the mainstream, pushing the boundaries, pushing the barriers. Now, I don’t want to over read it, that’s with the benefit of hindsight, but if you’re already outside of the mainstream culture from what you’re doing, then joining a political party like Sinn Féin in 1995 in Dublin, where the Special Branch would be outside your house, or you’d be stopped going in and out of the Sinn Féin office or the book shop when you went in to buy the paper, you already see yourself outside the mainstream.

“For me, one of the reasons I don’t listen to a lot of the music I listened to before is it’s now, for me, tired. It was exciting of its time, but music has moved on, it's changed. For me, it’s what’s the next bit that’s breaking the boundaries and moving things to another place musically or culturally. That’s what interests me.”

Check out the Spotify playlist assembled not by Eoin but by me based on our chat. If you’d like to support DEAN MAGAZINE, please consider becoming a paid sub.