All 50 #BeyondFriday Movies... Ranked

This time last year, when it was totally understandable to fear we were reaching End of Days, Ireland was looking to Patrick Swayze for comfort. Alison Spittle had begun organising movie watch-alongs on Twitter under the hashtag #CovideoParty. Dirty Dancing was an early selection and it inspired a small group of film buffs with similar tastes to watch Swayze’s lesser known Next of Kin together via a similar portal. Friday, March 20 at 11pm was selected as an appropriate time—later than #CovideoParty to avoid a clash—the hashtag #NextofKinParty was settled on, and some curated trailers were even posted beforehand to enhance the cinematic feel. A success, the group decided to do it again the following week, this time choosing to watch sci-fi body horror From Beyond in honor of its director Stuart Gordon, who had just passed away. The hashtag #BeyondFriday was spawned and that’s how it has stayed for a further 48 films to date. That name has been the perfect accident. Friday is obviously an excellent day and these movies take you beyond Friday. Prepare for a wild start to the weekend.

The #BeyondFriday high council consists of Paul Duane, Jason Coyle, Daniel Fitzpatrick and, previously, John Byrne (currently on hiatus). Encapsulating what kind of movies they pick for #BeyondFriday is not straightforward. Broadly, I’d describe most of the selections as cult classics, genre pictures, B-movies, grindhouse joints, and some stuff that has been unfairly forgotten in time—the fact that most of the films are freely available on YouTube reflects how ignored they are by rights holders. I admire the guys for not leaning on “so bad, they’re good” movies, a cinematic form that’s lost so much sincerity in recent years that it’s no fun anymore. As far as I can tell, the films here are chosen because selectors think they are great and want people to see them. They are works of invention, forged by real filmmakers often trying to realise their vision on limited budgets and in genres that don’t win awards.

On a personal note, I’ve been very grateful to have #BeyondFriday as a rare bright spot on the Covid calendar. I first started watching the third week and it’s been a joy to see the event grow from just a handful of movie fans talking amongst themselves to trying to topple The Late Late Show in the Irish trending charts every Friday night.

To mark #BeyondFriday reaching a milestone, I’ve ranked all 50 movies with a few words on each. These are not reviews, just off-the-cuff notes, stray thoughts, and notions I’ve had. Some of these blurbs were written months after watching these movies over cans and I’ve done minimum research to pad out the text. #BeyondFriday is supposed to be fun so pouring over each film painstakingly closely doesn’t seem in the right spirit. After all, this is a celebration of all the strange and forbidden imagery we’ve been exposed to and friends we’ve made on the way. And if you’ve not been part of it, maybe you’ll find something to throw on one night. Let’s go.

50. Down (Dick Maas, 2001)

An abomination. Fuck, where to start? It’s a movie about a sentient killer lift. If you tried to, um, elevator pitch Down, the idea would probably seem pretty thin, but I believe any concept can work if executed correctly. It’s just hard to imagine how Down could have been much worse. The set pieces involving the lift are dumb, the cinematography is inappropriately clean for what is essentially a B-movie, and the story makes zero sense. The cast is full of actors either overqualified or embarrassed, with Naomi Watts particularly uncomfortable with the material. And while this might be a small thing, I’ll say it anyway: I’m extremely adverse to 2000s fashion, of which this movie features the worst of the worst. Down is a remake of the 1983 Dutch movie De Lift (which, in my broken Dutch, I can tell you means “The Lift”), supposedly a better film. Both original and remake were written and directed by a man named Dick Maas. But there’s nothing funny about that.

49. Freaked (Tom Stern & Alex Winter, 1993)

I fear my tolerance for zany live action movies might be extremely limited. Freaked is based on an MTV sketch comedy show called The Idiot Box, which I haven’t seen, but I assume that the movie’s schtick is better suited to short bursts. Freaked centers on a mutant farm where a vain actor (Alex Winter, also co-director) is transformed into a kind of half-gremlin to lead a squad that includes Mr. T as a bearded lady, an uncredited Keanu Reeves in heavy dog makeup, and Bobcat Goldthwait as a guy with a sock puppet for a head. Visually, the movie pitches up somewhere between a live Aaahh Real Monsters and Mad magazine. I do admire the filmmakers willingness to go all in and create something so visually singular, but it’s not a pleasant experience. May the gods help me, I hated even looking at this thing. And the humour isn’t sharp enough—many of the jokes feel off-the-cuff, logic be damned. I did like the marvellous anti-corporate message though.

48. Next of Kin (John Irvin, 1989)

The problem with Next of Kin is that a distinct lack of cool shit happens. Patrick Swayze never really gets to lean into his character Truman Gates—an Appalachian “redneck” turned city cop—because the movie doesn’t give him enough ass to kick. The premise should have adhered to the K.I.S.S. principle: Keep It Simple, Stupid. In this case, that would have seen siblings played by Swayze and Liam Neeson embark on a bloody revenge campaign after a third brother (Bill Paxton) is killed by the mob. Instead, the movie’s middle third becomes bogged down in moralising vigilantism and flat action scenes. It never really recovers. You do, though, get to witness a lot of actors looking younger than you’re used to seeing them (Neeson! Ben Stiller! Helen Hunt!), so try to enjoy that.

47. O.C. and Stiggs (Robert Altman, 1987)

How do you pin down a movie like O.C. and Stiggs—ostensibly a teen comedy with zero laughs? It’s directed by a genuine master in Robert Altman yet features two ultra bland characters in a John Hughes-lite adventure that’s always busy but with little purpose. It’s the kind of movie you expect a first time director to make, when they’ve a bigger budget than sense and decide to go all in just in case they’re never given a second opportunity. And this is Altman we’re talking about, making the decision to take his stars to Mexico and back for the thinest reasons, shooting a huge wedding scene with a dance number and machine gun, shoehorning in bizarre costume changes as if he wanted to run up the clothing budget for the hell of it. There’s a fascination with lobsters as a delicacy, while the great King Sunny Adé is roped in to do a mid-movie musical number (in insolation, one of the best scenes). Staring at so much vapid excess, I felt the movie epitomized the Reagan era. The grotesqueness of it was all only balanced by Melvin Van Peeble’s homeless wino, who is unfortunately underused. It’s only in the final act that Altman’s disgust at the era is detectable and the satirical bent of O.C. and Stiggs snaps into focus. Our kind-of heroes instigate a party at the home of a well-to-do family living in a soulless suburban Tangiers in the middle of the desert—Phoenix, that is—the synthetic nature of it as much an image of the American Dream as Las Vegas. Finally backed into a corner, the pair call in Dennis Hopper, playing his character from Apocalypse Now in all but name, to chopper into suburbia, forcing picturesque America to finally reckon with some of the country’s sin. I find O.C. and Stiggs a tough movie to place on this list because of how much its closing half hour recontextualised what came before. It’s a more interesting movie to think about than it is to watch. Here’s the pertinent question: is that on me or Altman?

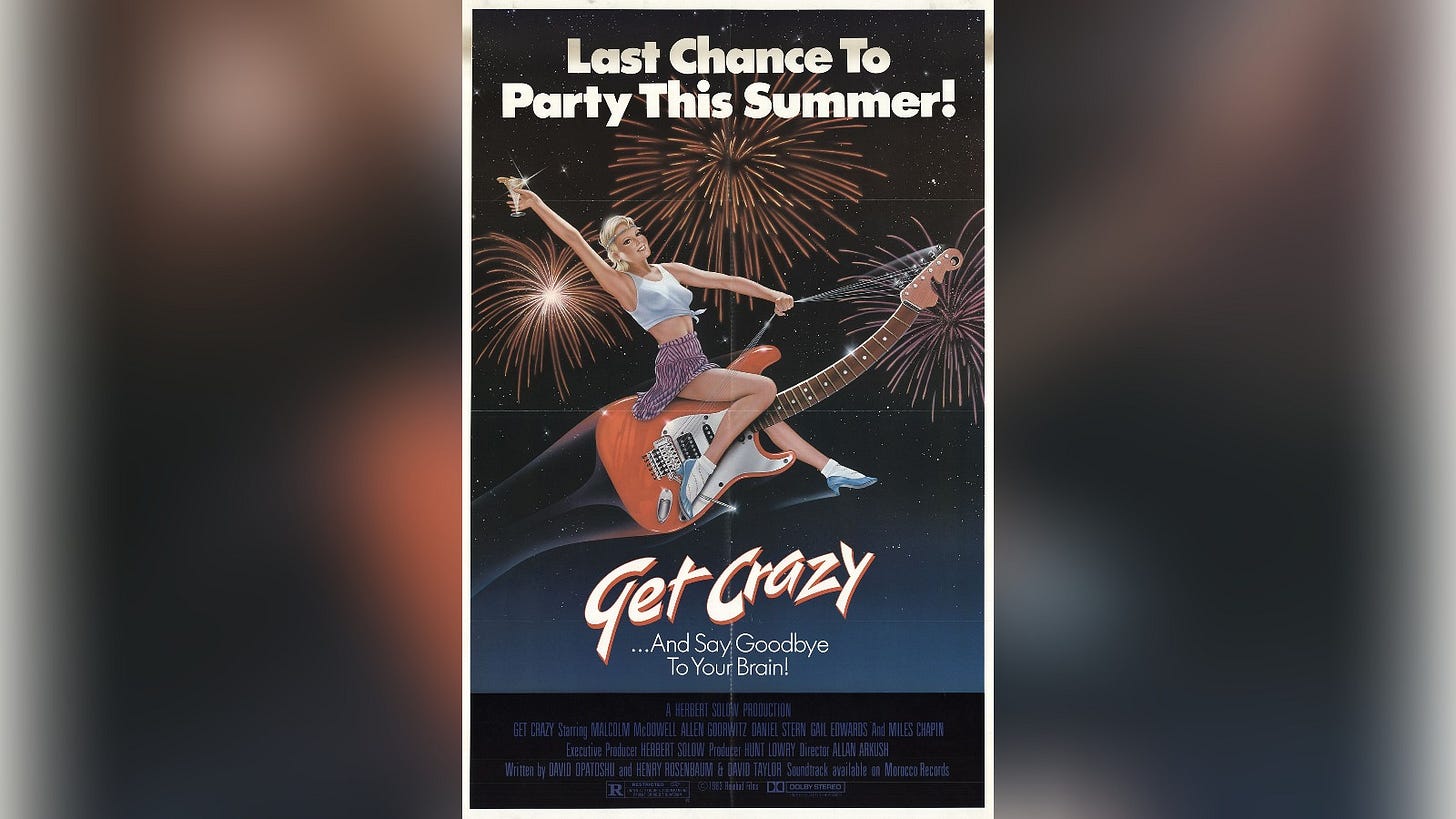

46. Get Crazy (Allan Arkush, 1983)

Following the organisation and hosting of a New Year’s Eve concert, “Get Crazy” is a stitched together collection of off-the-wall moments. One character goes flying off a balcony into a bunch of balloons for absolutely no reason—that’s what we’re talking about here. (The poster says “say goodbye to your brain” and I’ve long suspected that any advice on leaving your brain outside of the cinema theatre is a trite way of shielding a dumb movie from criticism.) However, the concert scenes are super: there’s a scintillating blues band, peppy 1980s bubble-gum pop girl group, Malcolm McDowell playing an ageing rock star with conviction. In the middle of it all is Lou Reed, starring as a version of himself in all but name, whose journey to the venue ends in a lovely closing credits payoff. A shame these musical highlights couldn’t have been wrapped in something that felt like a proper film.

45. Rawhead Rex (George Pavlou, 1986)

An Irish movie! And an example of that old horror movie lesson: it’s what the audience doesn’t see that’s really scary. RawHead Rex could have been a solid little genre flick, but director George Pavlou bucks the conventional filmmaking wisdom of slowly revealing his monster by shooting it like a delicacy in a Tesco’s ad. And that’s a big problem because though Rawhead Rex is said to be a demon from Hell, unleashed near Rathmore when a local man decides to plow a forbidden field, the monster looks like a giant rubber action figure dressed for a heavy metal gig. Not even the Power Rangers would have taken this thing seriously, so don’t expect an audience to buy anything the movie does. Still, there is some fun to be derived from its ridiculousness, with Ronan Wilmot having the time of his life as the mad priest. RawHead Rex also stars, um, my mate Jesse Melia’s dad Frank Melia as a local journalist.

44. Death Ship (Alvin Rakoff, 1980)

After a promising opening that’s reminiscent of the party scenes that kickstarted Under Siege, Death Ship is a surprisingly dull flip on haunted house tropes. The movies follows the mega cast—Richard Crenna, George Kennedy, Saul Rubinek, and others—as they wander the corridors of the Nazi prison vessel without ever being quite scary or ludicrous enough. Nazisploitation is a genre that came out of Europe and Death Ship might have been an American flick that fit in that particular canon if it went all in. Instead, the movie just kind of exists on screen, never really pushing your buttons.

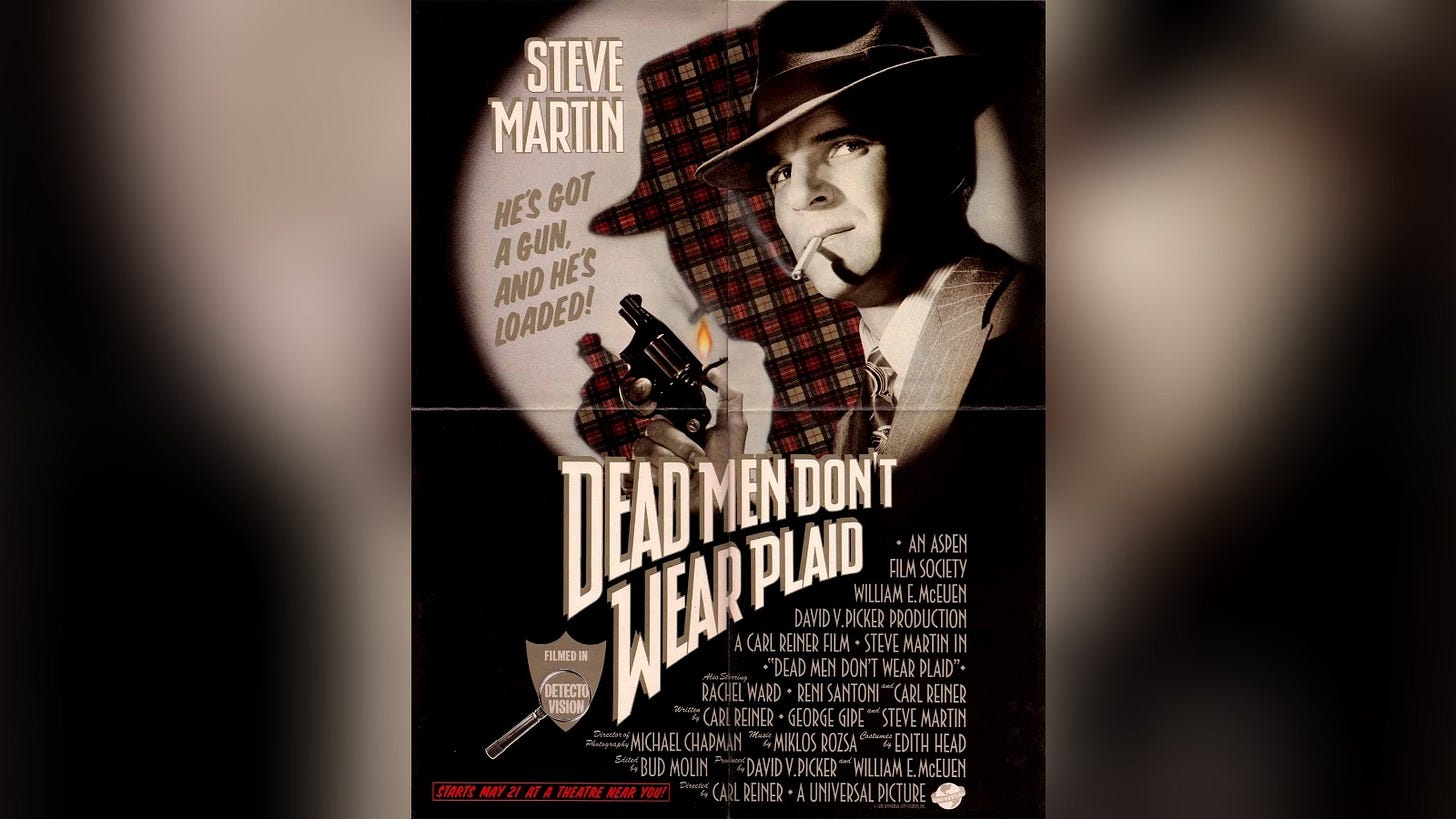

43. Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (Carl Reiner, 1982)

Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid wants to be both a parody and recreation of golden age Hollywood movies at once. In this confusion, Steve Martin’s performance as the booze-soaked private eye gets stuck somewhere in the middle—his comic instinct repressed as he is largely forced to play it straight, flashes of slapstick surfacing like they are trapped within, bursting to escape. This tonal mess is exacerbated by its attempt to cut in footage from dozens of old movies, presenting the illusion that Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid stars Humphrey Bogart, Joan Crawford and over a dozen other legends. I’ve seen this technique before, notably Kung Pow! Enter the Fist, when it was strictly played as a joke. Here, it’s used in a more serious manner. Conversations between Martin and his historic co-stars veer from unnatural to senseless, rendering the plot indecipherable. Selected to honor his passing, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid is directed by the great Carl Reiner, who sizzles in the small role as the villain. And I did love the era-accurate look of the movie. But the best thing about it is that it inspired me to watch the excellent I Walk Alone, one of its sources for old footage.

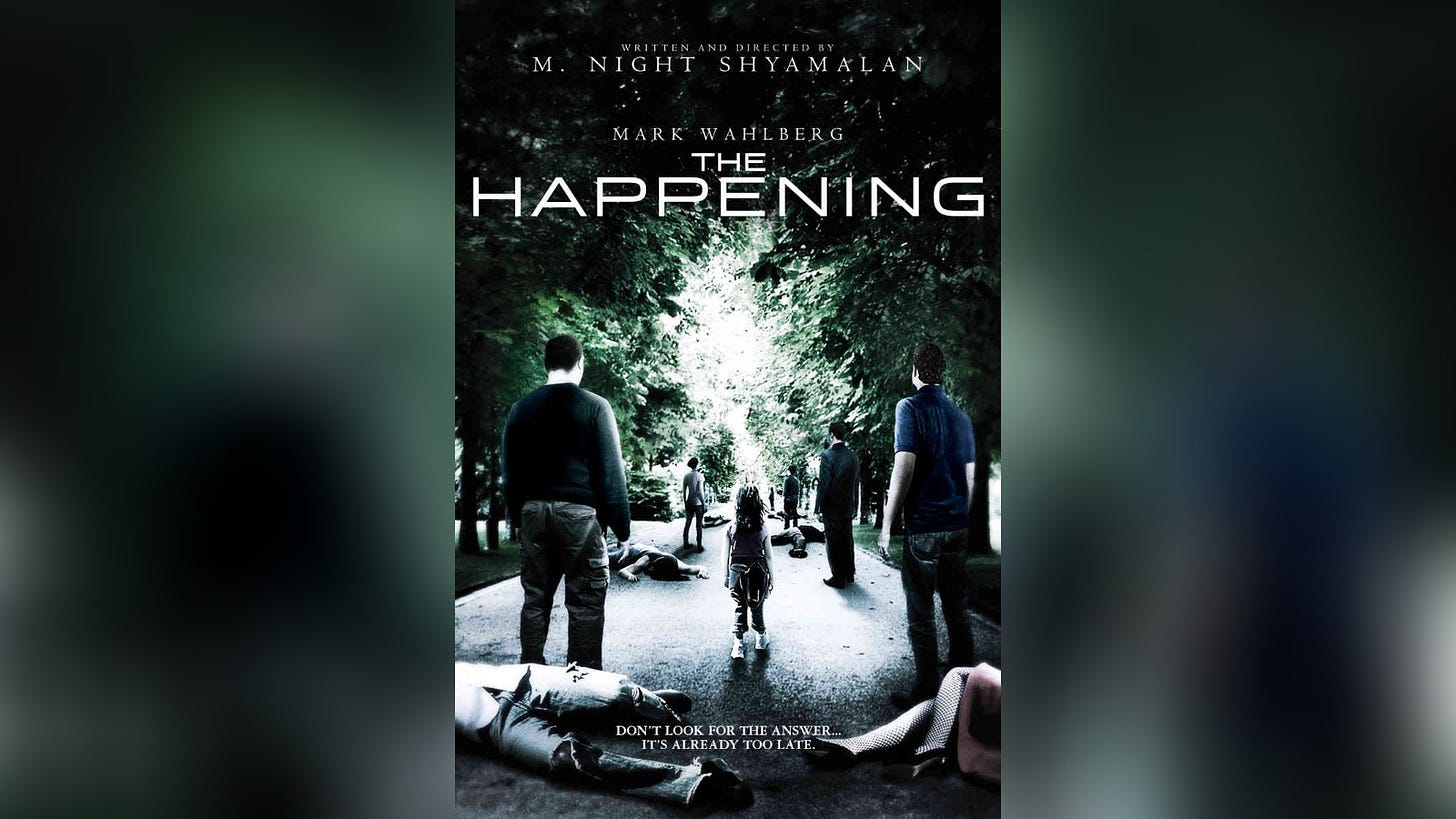

42. The Happening (M. Night Shyamalan, 2008)

I’m an M. Night Shyamalan fan but even I can’t defend The Happening, except to say that it’s mildly better than its shambolic reputation suggests. Following a group of survivors as they try to outrun a neurotoxin that compels people to commit suicide, I enjoyed the strange rhythm, bizarre acting, and throwback B-movie aesthetic that the film is ostensibly reaching for. But even for a work with modest ambition, the script feels about like it needed about seven more drafts. Most jarringly, the plot just kind of stops dead in its tracks in the third act before walloping you over the head with an environmentalist message right at the death. It is amusing to see Americans arming themselves to fight the deadly viral pathogen though. Maybe The Happening is a documentary?

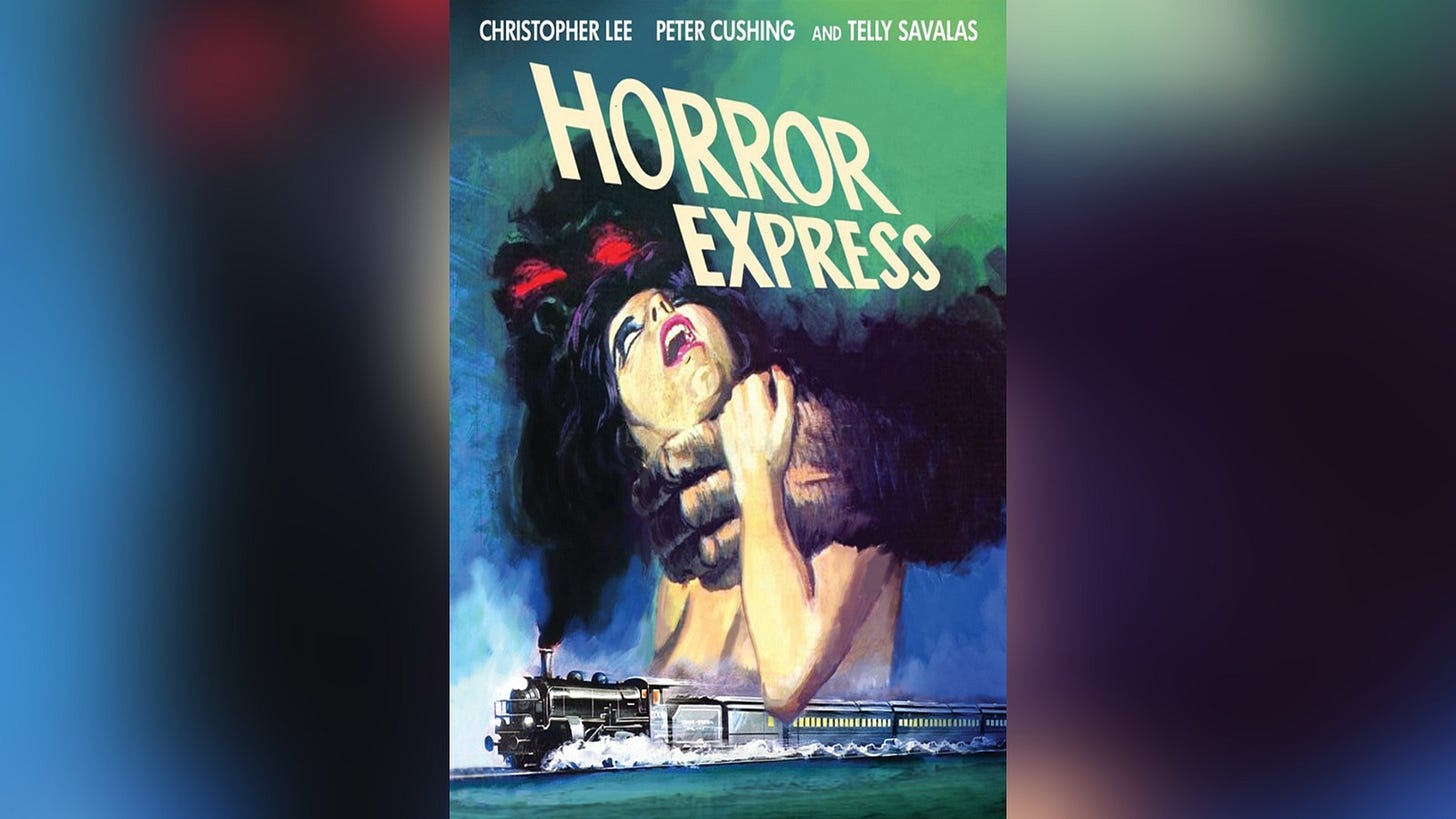

41. Horror Express (Eugenio Martin, 1972)

Creature feature dream team Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing travel on the Trans-Siberian Express. In the cargo hold, the frozen remains of an ancient fossil that just might be the missing link in human evolution. From the hand of Spanish director Eugenio Martin, Horror Express unexpectedly works in sci-fi elements—not to mention a mystic not very subtly modelled on Rasputin—to an otherwise by-the-numbers throwback European monster movie. Its best asset is the gorgeous cinematography, costumes and set design that lift the railway setting.

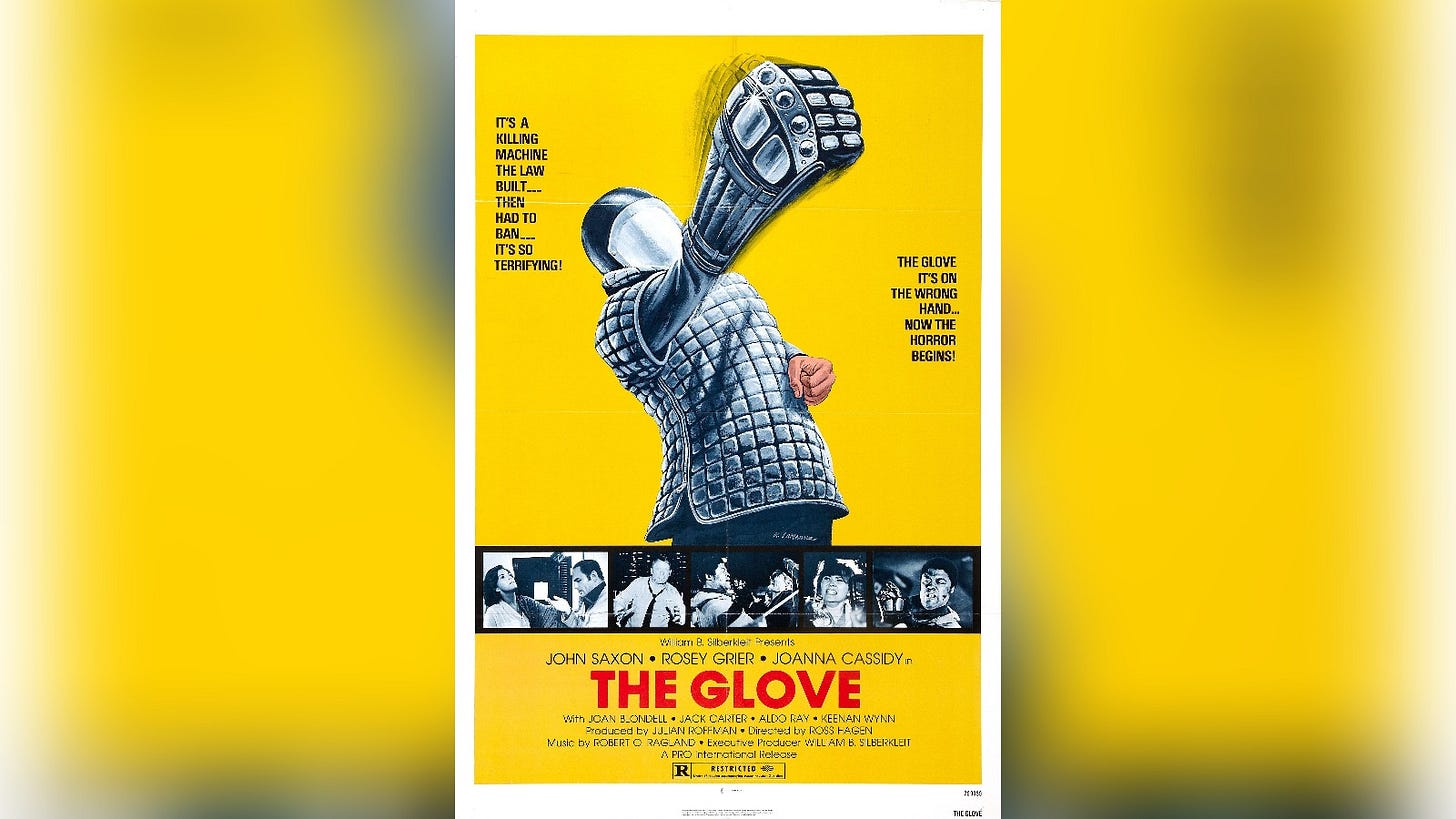

40. The Glove (Ross Hagen, 1979)

The Glove starts out great—mountainous ex-American Football player Rosey Grier uses a leather-laced metal mitten to smash a car to pieces like it’s a Street Fighter 2 bonus stage with his hapless victim still inside the vehicle. And the climactic face off, which I won’t say too much about, is a thrilling finale. Unfortunately, between these two bookends, much of The Glove is flat. Super cool bounty hunter John Saxon (whose sad death last July inspired this selection) traverses Los Angeles like 1970s Philip Marlowe, his voiceover work aligning the piece with classic film noir detective movies. But The Glove just can’t catch fire. Saxon, charming as ever, is allowed to strut through the first hour and a half playing cards, seducing women, and pontificating on his fractured home life at the expense of some of The Glove’s best elements—that is, Grier and his ability to smash things to pieces with a steel glove. Less plot, more glove!

39. From Beyond (Stuart Gordon, 1986)

The opening few minutes of From Beyond appear to set up a throwback 1950s-style sci-fi flick with an almost Nickelodeon-esque comic streak as two scientists working in an attic mess around with their latest contraption and annoy their neighbor. What emerges, though, is a genuinely unsettling body horror. Damn, this thing stays with you. The plot is threadbare: a mad doctor (Ted Sorel) invents a machine called The Resonator that allows him to access a parallel dimension of pleasure and the stitched-together trio of heroes (Jeffrey Combs, Barbara Crampton, and the great Ken Foree) attempt to solve the mystery. The mechanics of The Resonator and realities of this parallel dimension—that is, why a lot of the weird shit ends up happening—isn’t really investigated, but who cares? The outstanding make-up and special effects really make the skin crawl and blood chill. The physical deterioration of Combs’ character was particularly disturbing to me. Mix in some wild sexual imagery and you’ve got a concoction I can only describe as icky. Is this a good movie? Depends on if you enjoy being distraught.

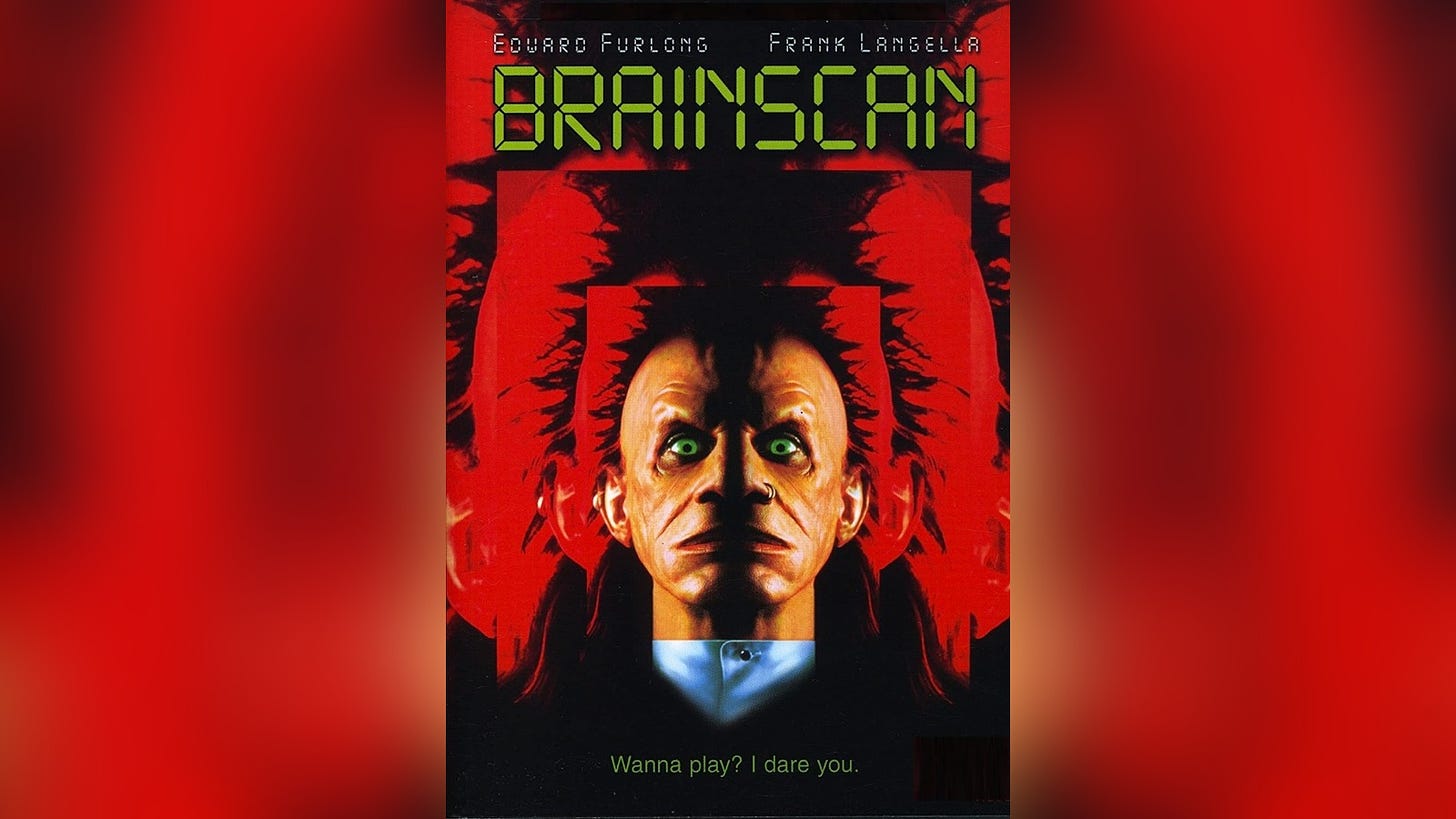

38. Brainscan (John Flynn, 1984)

There’s a great movie about pre-Y2K technology hysteria and video game violence in here somewhere. I really enjoyed Brainscan’s 1990s teen dirtbag stylings, grungy soundtrack, and focus on retro technology like CD-Roms. Which is why it feels like a cop out when it personifies its themes with a character called The Trickster, a physical entity summoned from a video game that sends Edward Furlong’s lonely gamer into a murderous trance. Having the media's effect on the psyche take flesh and blood form so he can simply spell out the movie’s themes—let alone one who looks like a melted hair metal musician—is insanely lazy screenwriter. With that in place, director John Flynn slips into a by-the-numbers slasher. The murder scenes are worth mentioning though. The violence in #BeyondFriday movies tends to be pulpy and cartoonish, but this movie bucks that trend by having some extremely graphic stabbings. Regardless, a little bit more clever plotting and this could have been something special.

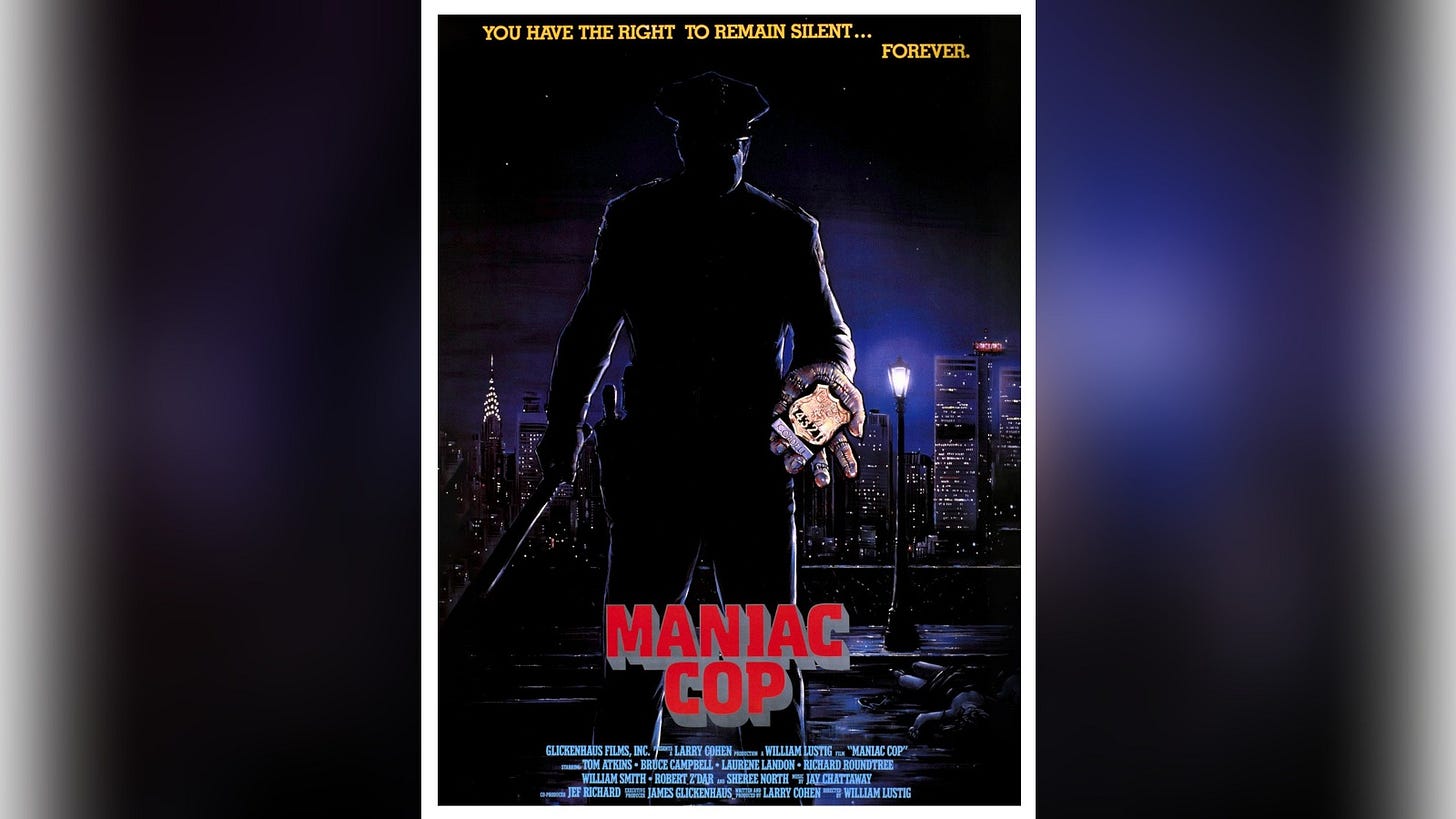

37. Maniac Cop (William Lustig, 1988)

Maniac Cop might be regarded as a B movie classic—Bruce Campbell!—but its production is surprisingly slick. A quick Google tells me that director William Lustig, working off a script by Larry Cohen, made the movie on about one-sixth of the budget of The Terminator and they really squeezed every last dollar to create a similarly cold and derelict urban setting. Unfortunately, the polished production reflects a formulaic script, which settles into a “solving the mystery to catch the killer” thriller. A familiar outline would be fine if the movie was inventive in other ways, but the on-screen violence lacks both impact and originality, and there are few true capital-M Moments throughout. Really, the best thing about Maniac Cop is the title character, a kind of tortured Frankenstein’s monster with a badge and gun in contemporary New York. I’d have liked to see his turmoil fleshed out a bit more (that may happen in the sequels I’ve not seen). As it is, Maniac Cop is a fun enough way to pass the time and nothing more than that.

36. Messiah of Evil (Willard Huyck/Gloria Katz, 1973)

An auteur zombie flick (or are they vampires?), Messiah of Evil is beautiful to gaze upon. So many shots would make for a great poster on your wall, with co-directors Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz frequently using painted pop art to flatten the frame, trapping you in their creepy fantasy. Following a young woman as she journeys to a small town in search of her father, the film’s blueprint is fairly run-of-the-mill and the duel voiceover work that comes in and out will infuriate filmgoers who find that kind of thing to be lazy writing. The highlights are undeniably when supporting characters break free from the pack and find themselves hunted by the zombified townspeople. The movie theatre scene in particular is one of those great horror moments when the savage villains take their time when terrorizing the victim for no explicit purpose other than it works cinematically. In moments like these, Messiah of Evil does original things within its familiar outline.

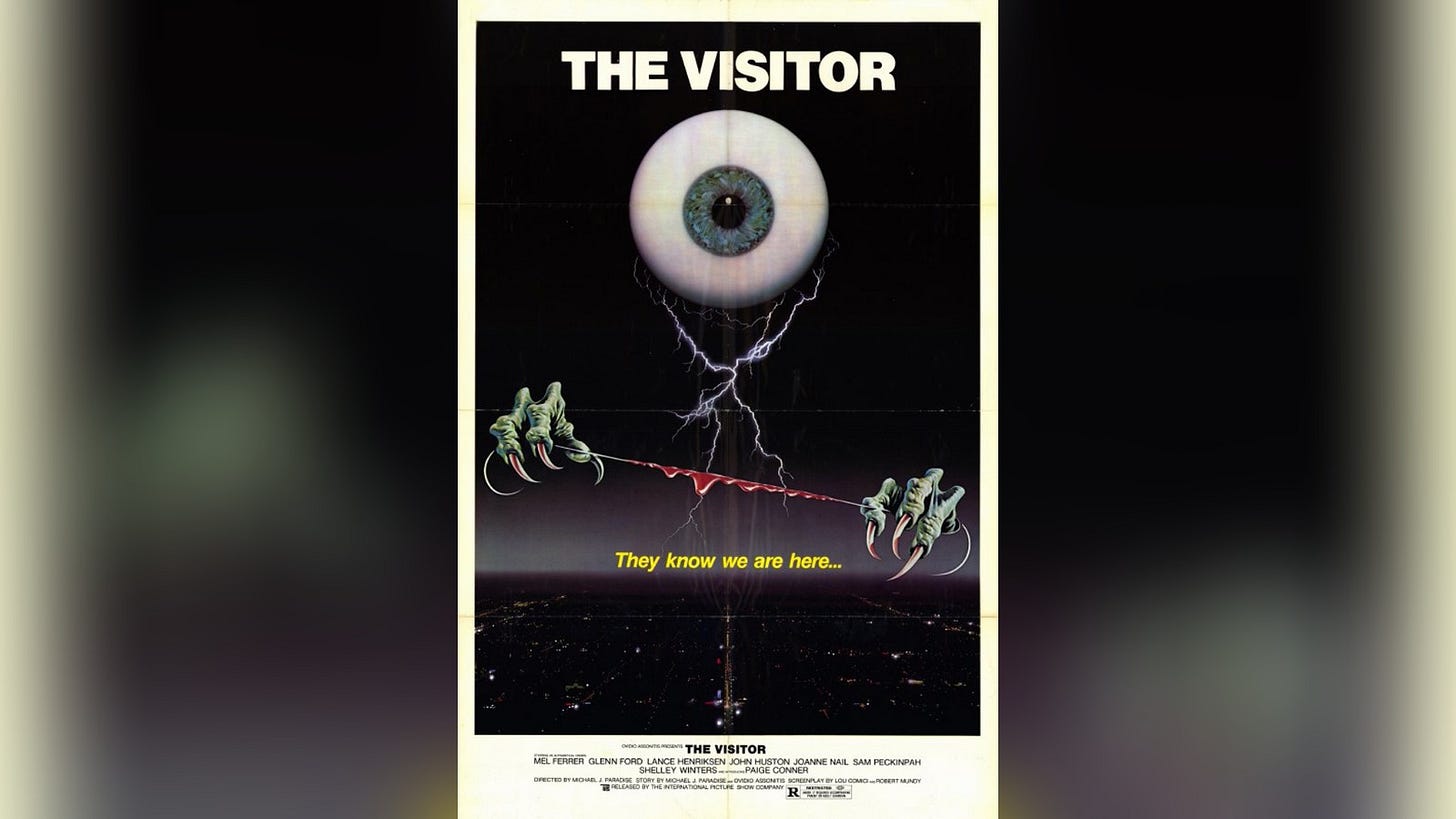

35. The Visitor (Giulio Paradisi, 1979)

You can’t knock the ambition. Euro-American production The Visitor is at once a supernatural horror in the vein of The Exorcist and The Omen, and an otherworldly science fiction saga. The plot follows an old guardian Jerzy Colsowicz (John Huston) who arrives on Earth to put a stop to a demonic child named Katy who carries the bloodline of a powerful intergalactic being. You know from the opening 10 minutes that the tone of The Visitor is going to be all over the place when it segues from a dusty space western scene to a basketball game in modern day Atlanta via a snazzy funk music break. By being too many things at once, the movie is never quite as creepy as it needs to be. And the plot lacks focus—Colsowicz spends most of the movie circling the action, the best scenes often coming when he makes contact with Katy, but his tactics aren’t particularly clear. The Visitor is a movie of many strands and some work really well—there’s some enjoyable melodrama mixed into the madness when Katy’s mother approaches her ex, a doctor inexplicably played by Sam Peckinpah, for help in aborting a demonic embryo—but the script could have done with more clarity on what it wanted to be.

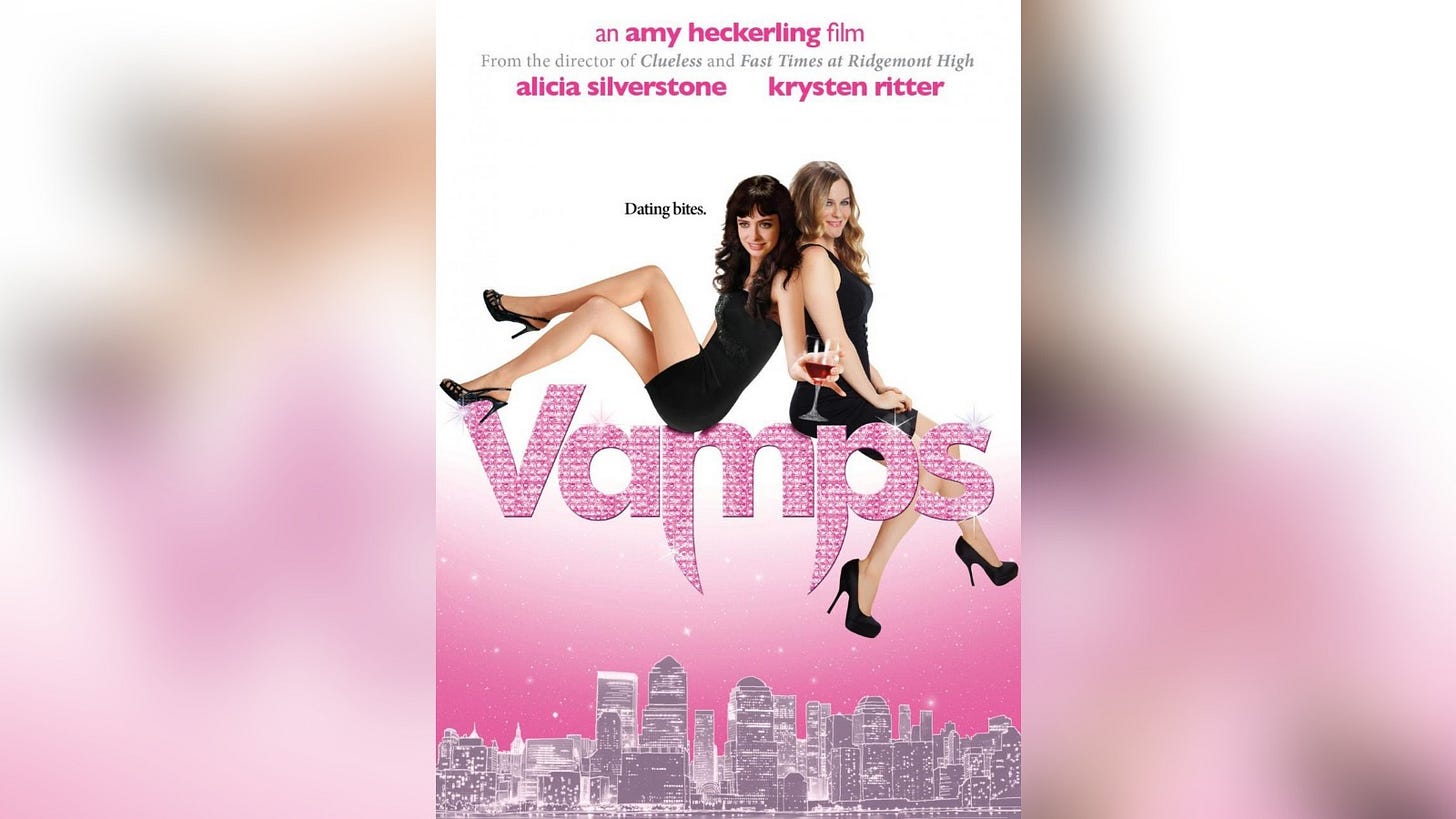

34. Vamps (Amy Heckerling, 2012)

I can’t believe I’d never heard of this before. Clueless director Amy Heckerling re-teams with Alicia Silverstone for this utterly tweaked comedy horror. If Clueless was a movie that subtly leaned on Jane Austin’s Emma, Vamps revels in its reimagining of every vampire trope cooked up since Stoker—Wallace Shawn (of all people) even plays Van Helsing. Vampire movies moved to a contemporary setting is nothing new, but Vamps nails its comedic tone. I might never heard of this as the movie just came and went—taking just three grand at the US box office apparently—but if there’s any justice in Transylvania, it’s a cult favourite waiting to happen.

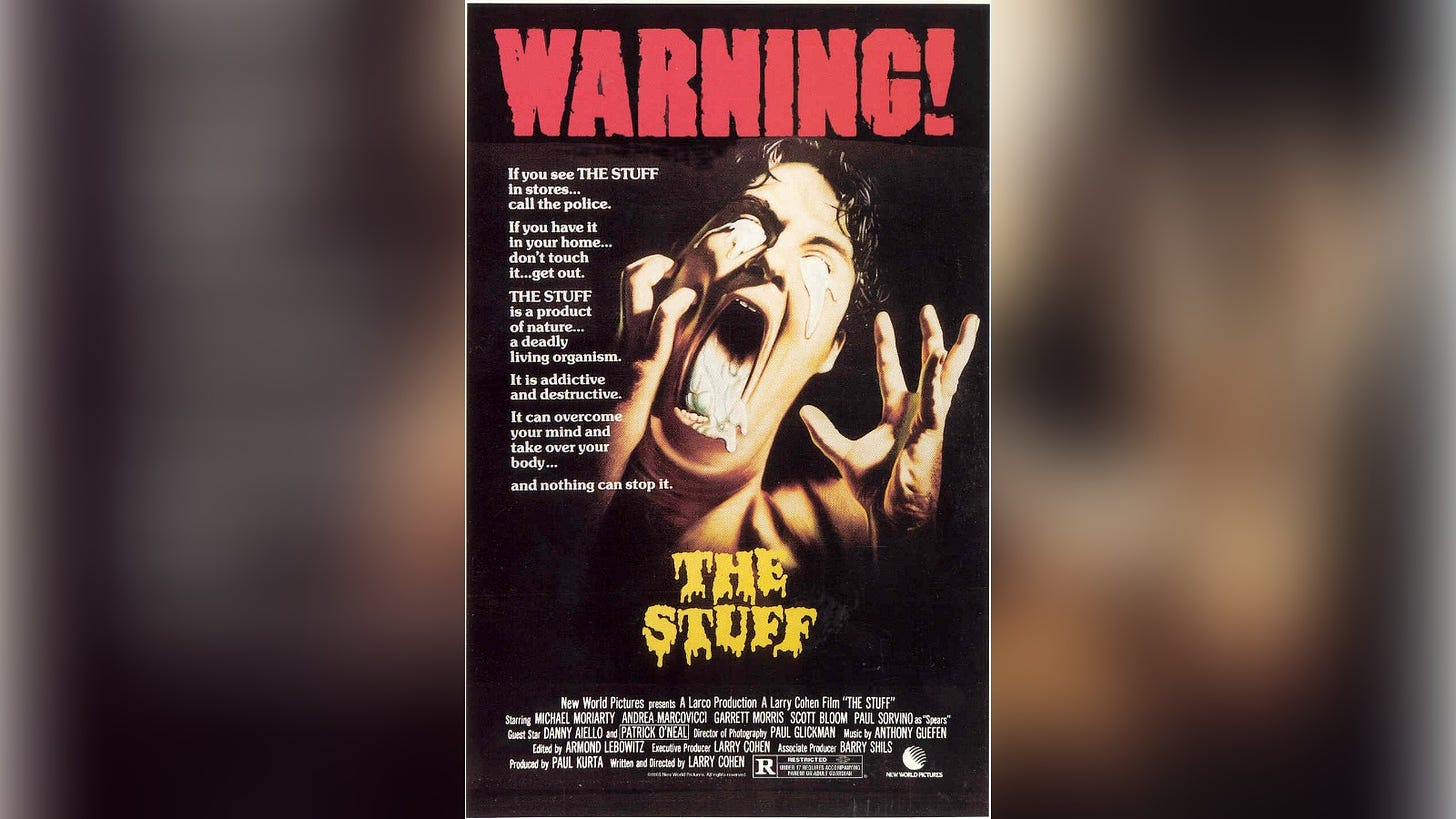

33. The Stuff (Larry Cohen, 1985)

Writer/director Larry Cohen’s satire on consumerism, corporate greed, and America as a fast food nation, The Stuff is not too subtle—companies will literally market mysterious goo oozing from the Earth as a dessert if people will buy it, says the movie—but its absolute dedication to ramming its message home helps elevate the enjoyable goofiness.

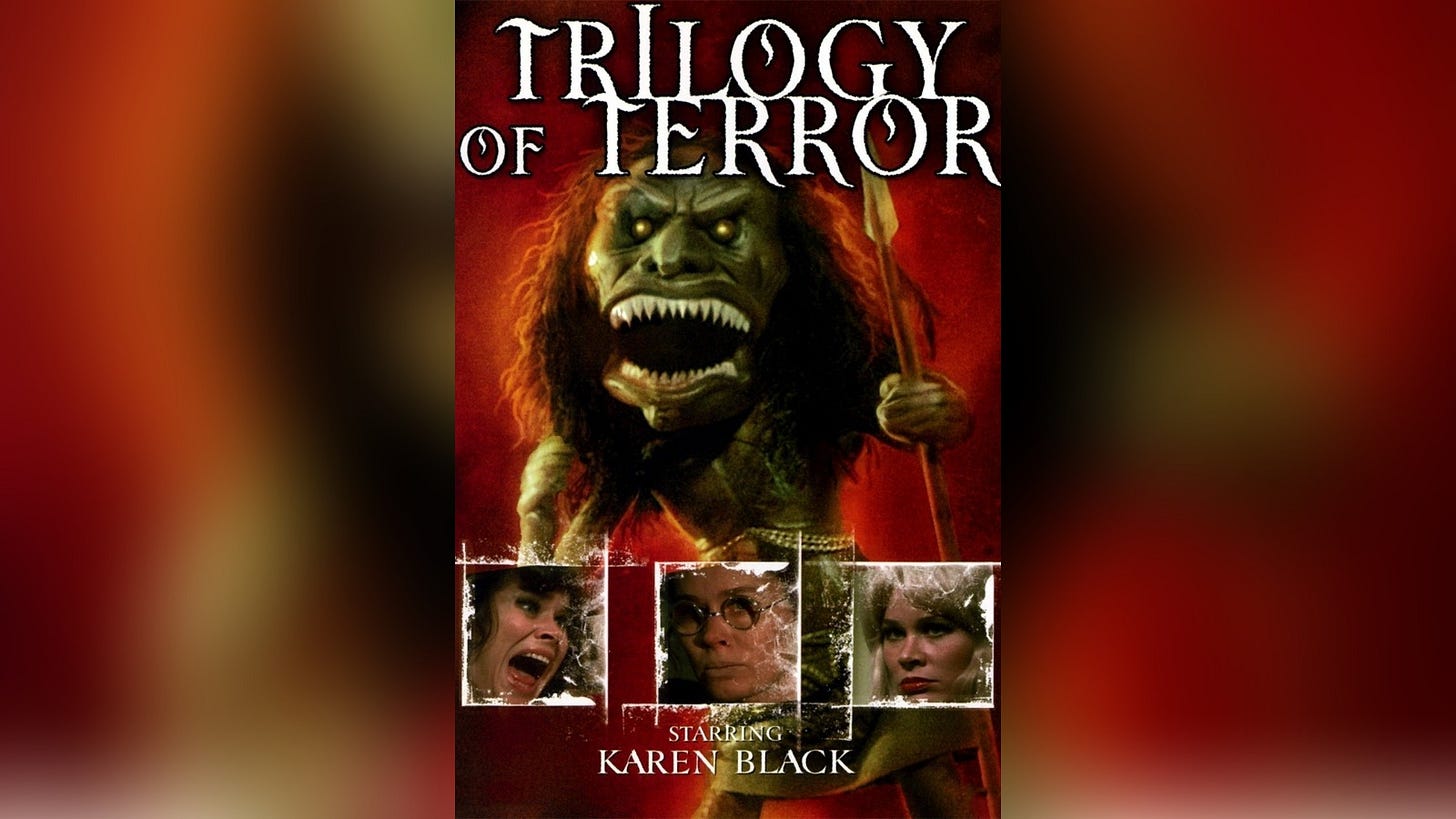

32. Trilogy of Terror (Dan Curtis, 1975)

This short, made-for-TV anthology horror features three separate segments, all starring Karen Black. She actually plays two different roles in the middle story, so it’s fair to say Black shows all the range of Krusty The Clown’s head shots. In fact, Black is the only (human) star of the final segment, which sees her terrorised by a small wooden doll, predicting the Child’s Play series. There’s variety in Trilogy of Terror: one segment sees Black enact revenge on a man who spiked her drink. By keeping each section short and tight, there’s an efficiency to the storytelling that’s refreshingly contrasts some of the more bloated pictures being released today.

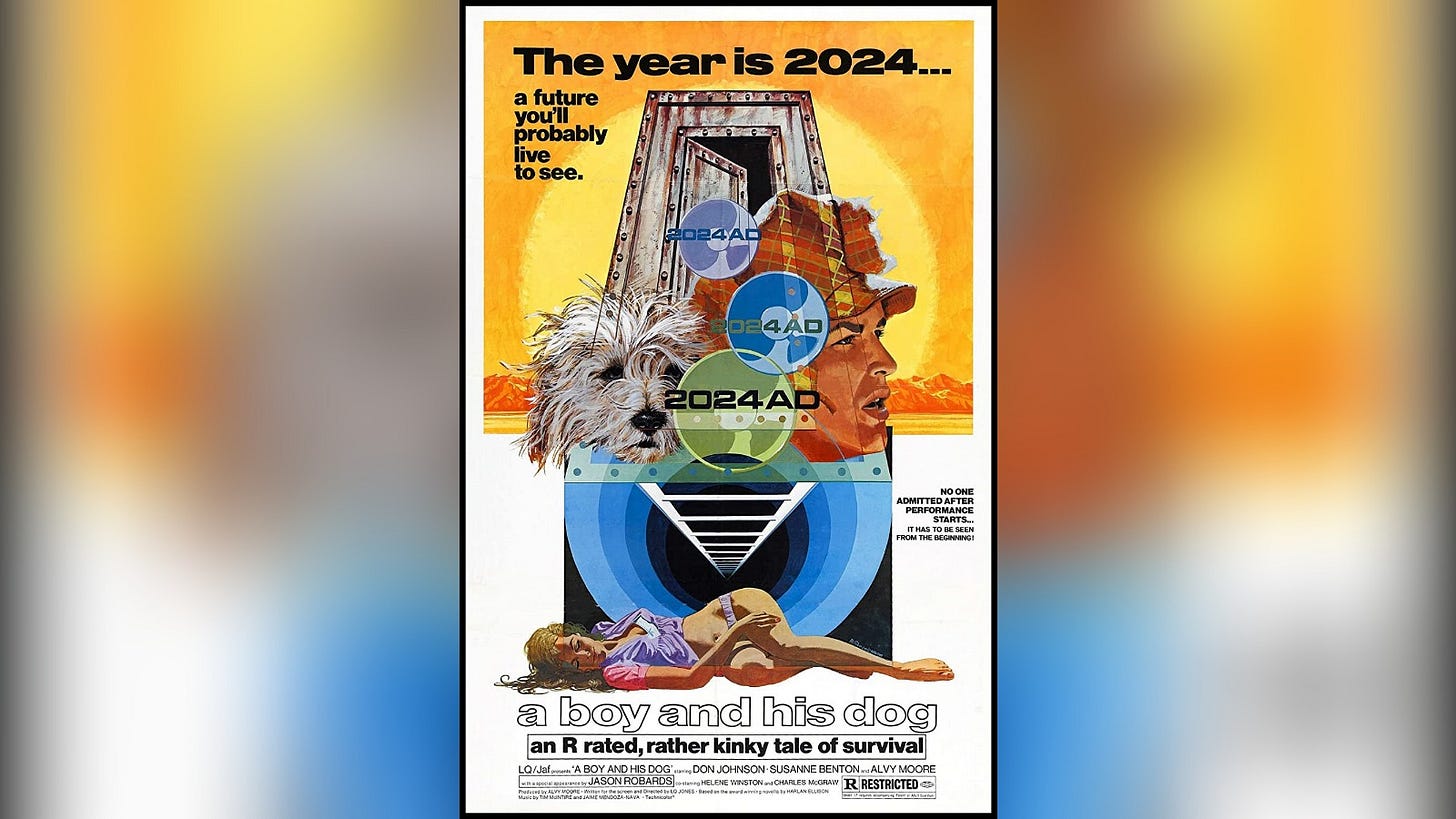

31. A Boy and His Dog (L.Q Jones, 1975)

A bizarre and chaotic post-apocalyptic black comedy, A Boy and His Dog benefits from its absolute dedication to the premise that a telepathic dog is helping an 18-year-old kid navigate the harsh terrain of post-nuclear war America. This is a movie about a talking dog that wants to be defined by the richness of its characters—a setup that would be impossible without the dedicated performance of a young Don Johnson, who sells the relationship with the shaggy animal completely. And though A Boy and His Dog is missing the strong satirical bent you find in a lot of post-apocalyptic movies, the ending is deliciously nihilistic. We’re all bastards, godspeed.

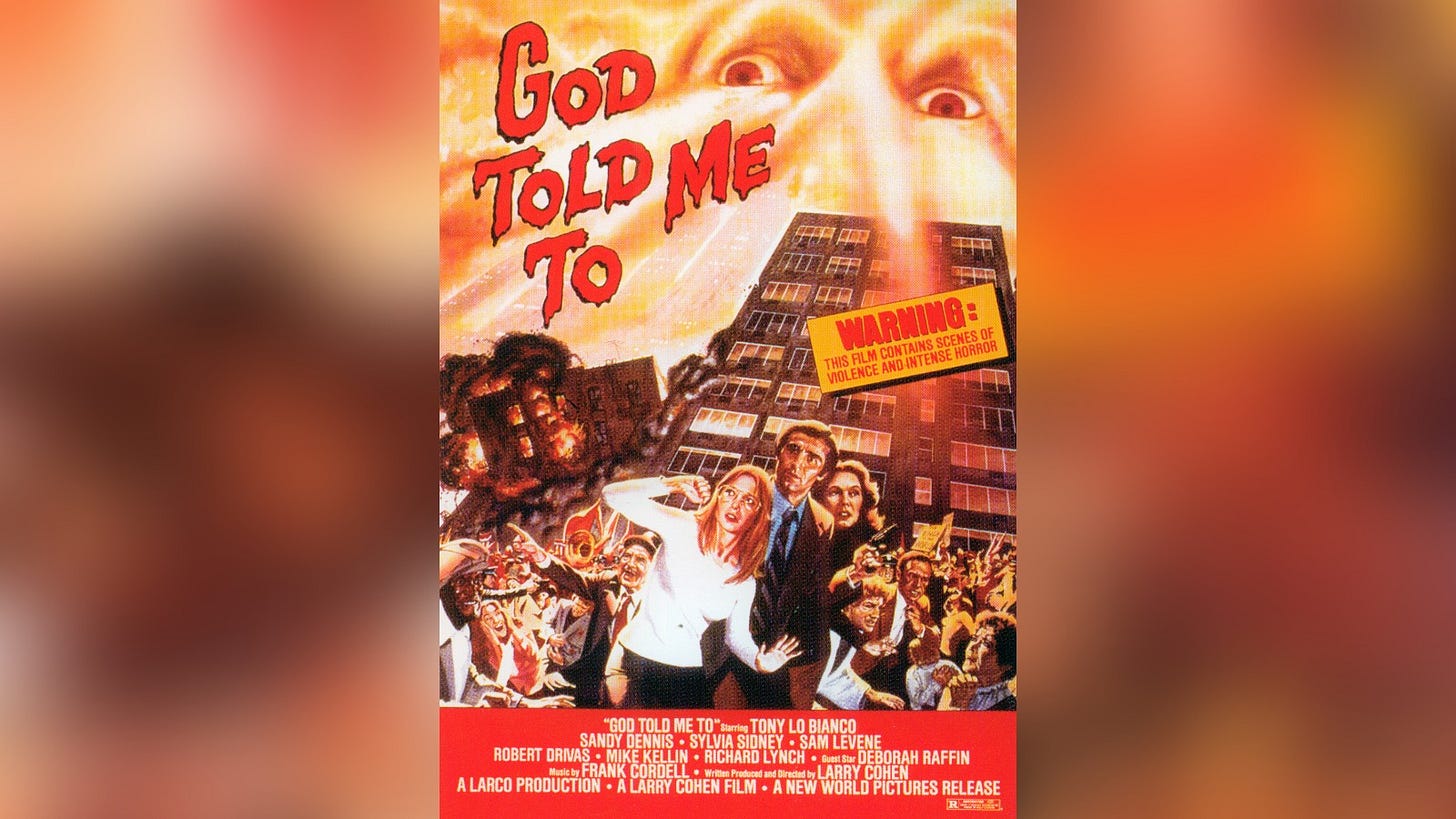

30. God Told Me To (Larry Cohen, 1976)

God Told Me To immediately reels you in. The opening scene sees a sniper in Manhattan picking off random victims, reminiscent of Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets. When Tony Lo Bianco’s highly competent detective scales the building to ask the killer’s motive, he utters the movie’s title before throwing himself off the roof. Slipping into a police procedural, Lo Bianco traverses New York, moving from crummy apartment buildings, to churches, to pool halls—the streets Travis Bickle looked upon with such disgust. Director Larry Cohen stalks his star with a soundtrack that veers from aggressive, Psycho-style orchestration to eerie low budget science fiction soundtracks from the same era—indeed, the 1950s flashbacks mimic the sci-fi of the day. As Lo Bianco plunges deeper into the mystery, Cohen plunders Catholic imagery to twist his alien tale.

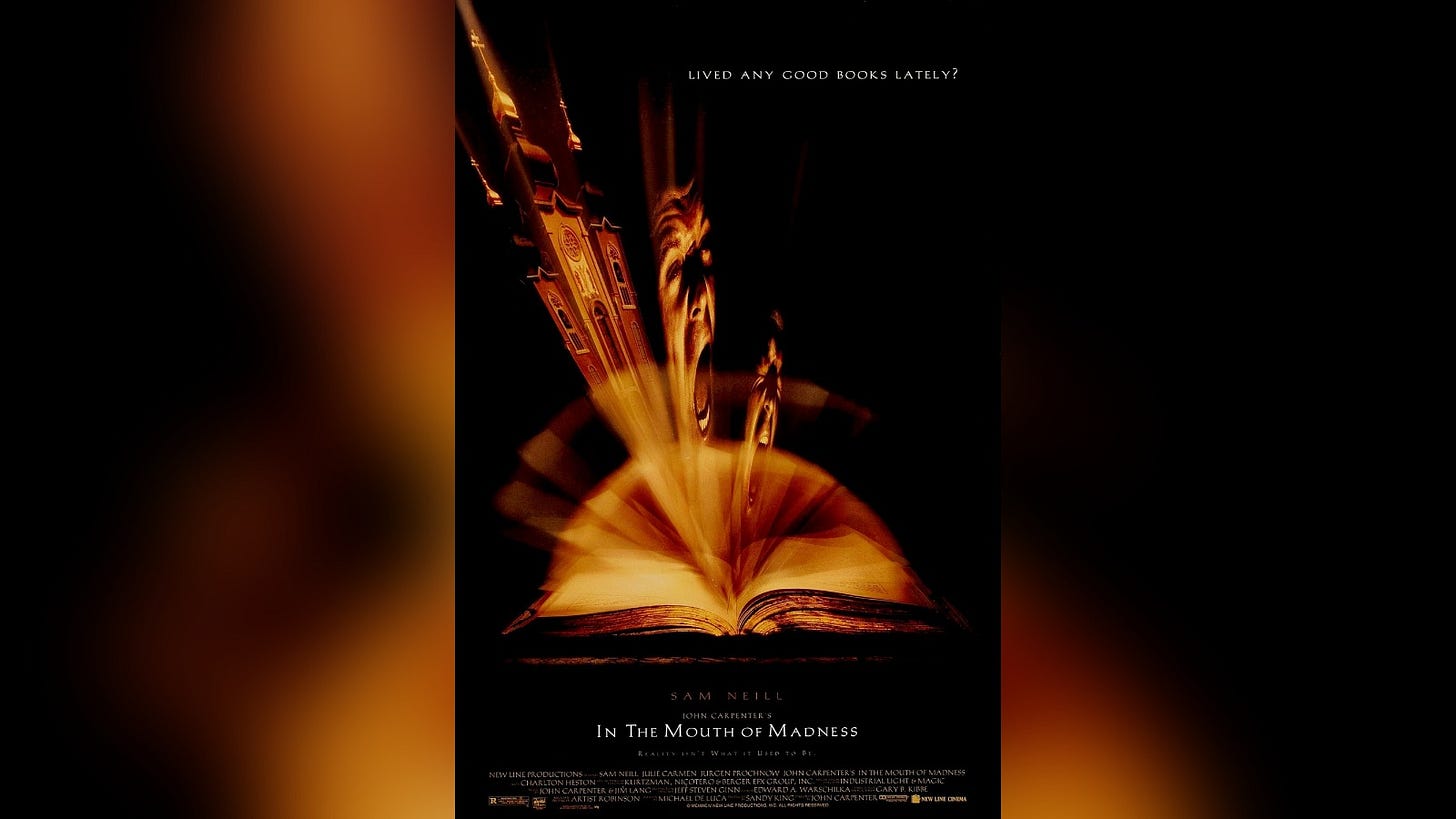

29. In The Mouth of Madness (John Carpenter, 1994)

“A reality is just what we tell each other it is,” says book editor Linda Styles (Julie Carmen). “Sane and insane could easily switch places, if the insane were to become the majority. You would find yourself locked in a padded cell, wondering what happened to the world.” This is the crux of John Carpenter’s In The Mouth of Madness. Loads of films play with the concept of what’s real, but few signpost their themes so obviously. I mean, the plot centres around the disappearance of a fiction writer, while Sam Neill’s protagonist is an insurance fraud investigator, a profession where you must test what’s real all the time. Despite big ambitions on paper, the movie pitches up somewhere between a pulpy horror novel and, when Neill makes it to the mysterious town Hobb’s End, an old point-and-click adventure game as he makes his way around the location, interacting with locals, witnessing an increasingly bizarre chain of events. The lack of clarity on what is the true nature of reality might frustrate you if you take In The Mouth of Madness too seriously, but the journey is full of interesting notions.

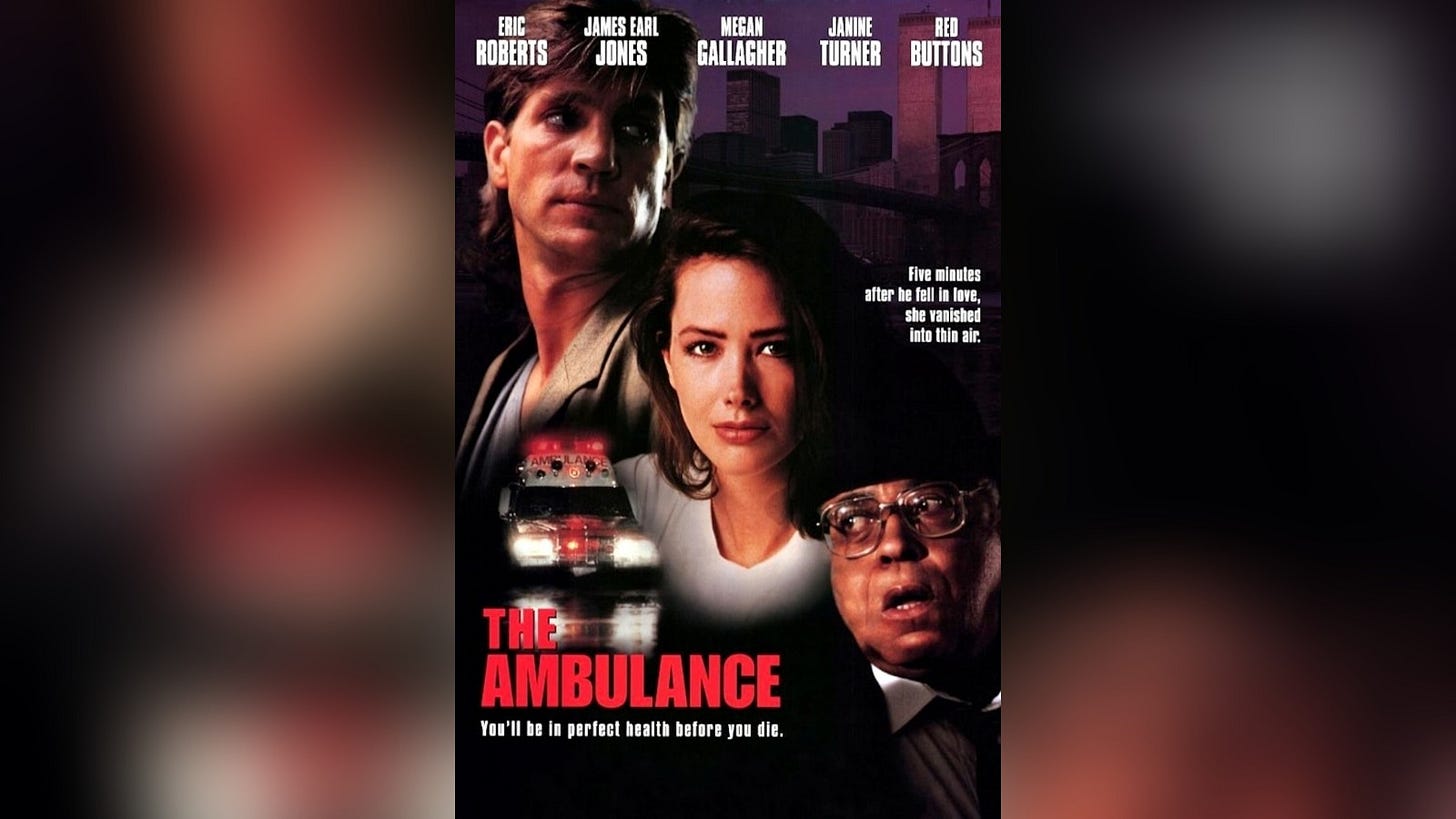

28. The Ambulance (Larry Cohen, 1990)

“A vehicle of mercy that’s really a murder machine.” That’s how Eric Roberts describes the eponymous vehicle he pursues in search of the woman who collapses while he’s shooting his shot. Larry Cohen shoots The Ambulance as part monster movie, part haunted house caper, not skimping on the green light or over-the-top screams.

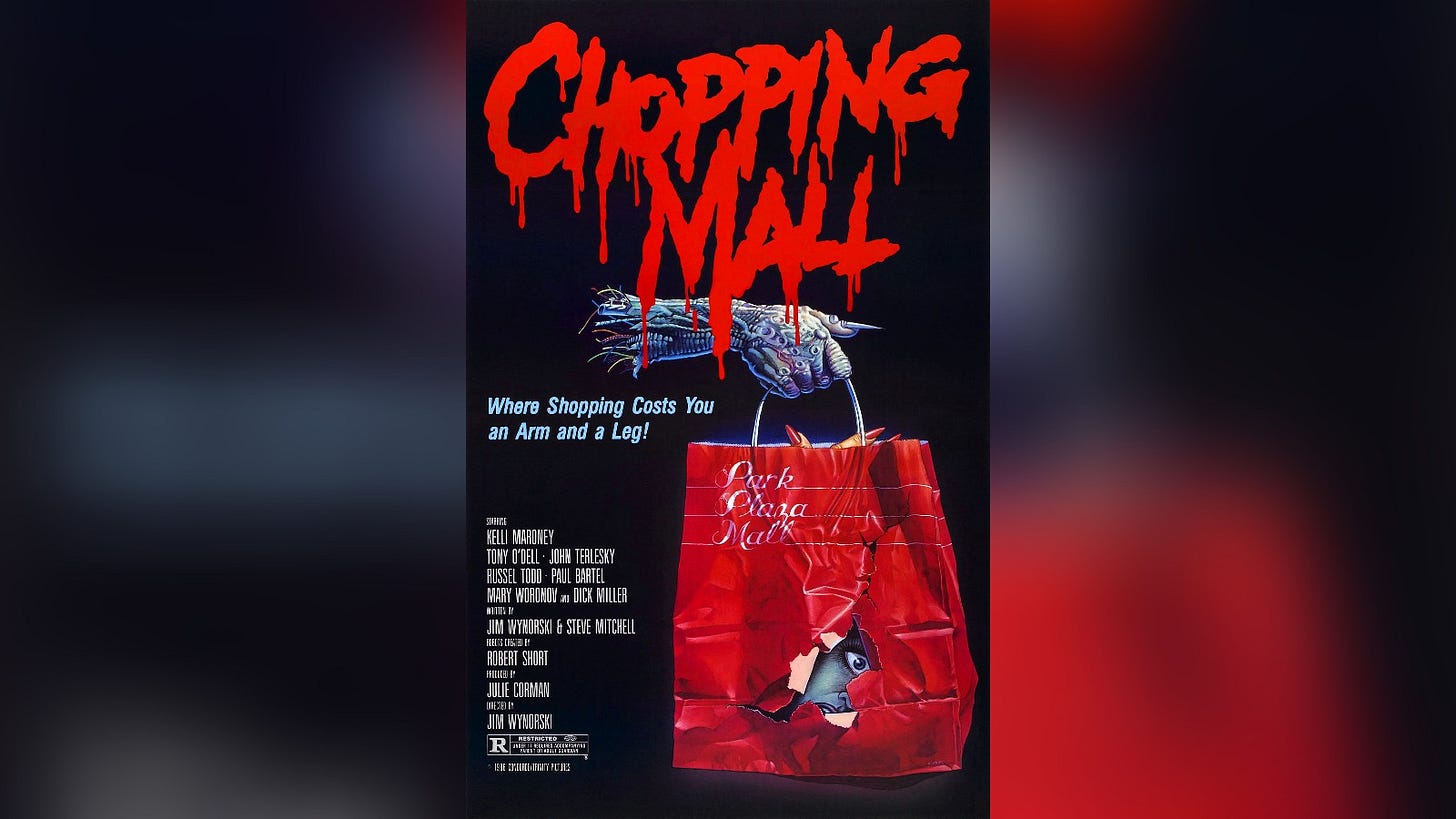

27. Chopping Mall (Jim Wynorski, 1986)

There’s not a lot of chopping but there is a mall. This movie is as lean as you like, doing the minimum amount of work possible to set up the premise of a group of young people trapped in a mall with killer security robots. Which is fine because Chopping Mall knows exactly what it is—a flick where the enjoyment is derived from how these extremely unthreatening looking bots are going to pick off the cast one by one. And the actors give it there all without ever seeming like they’re not in on the joke.

26. Penitentiary III (Jamaa Fanaka, 1987)

You don’t have to catch the first two instalments in James Fanaka’s Penitentiary series (I haven’t) to dig this little boxing/prison movie that revels in both subgenre’s most famous cliches. Ex-boxer Too Sweet (played, as he was in the first two Penitentiary movies, by Leon Isaac Kennedy) has renounced all violence—not that it matters when he is set up and sent down, imprisoned under the watch of a corrupt warden determined to get him to box in the organised prison bouts. So far, so familiar. But Penitentiary III unexpectedly works in elements of gothic horror, allowing Fanaka to shoot the tight corners of the prison like a haunted house, and there’s an unexpectedly surprising arc to the character Thud (Raymond Kessler), a dwarf who goes from a wild and ferocious opponent of Too Sweet’s mentor.

25. Xtro (Harry Bromley Davenport, 1982)

Alien abductions are falling and there’s been a decline in UFO sightings. Turns out, the proliferation of recording technology hasn’t led to an upturn in evidence that aliens are among us. Or maybe less people want to believe. You take this stuff as seriously as you want to take it. Or maybe you don’t take it at all. Whatever the case, Xtro encapsulates an era when alien abductions were a prominent part of western culture. I remember watching sensationalised shows about “real life” abductions as a kid on Sky One that freaked me out. Xtro rekindles those fears by playing with the most unsettling elements of alien abductions: body horror, cloning, extraterrestrial-human breeding. A typical trope of alien abduction stories is that the alleged victim claims their body is paralysed. Xtro feels like being trapped in that moment for 80 minutes. It’s strange but it’s also hypnotic. The poster parodies ET, which is understandable from a marketing point of view, but Xtro doesn’t feel led by any one movie. It is a genuinely unsettling, grimy piece of work.

24. Fortress (Stuart Gordon, 1992)

As much as I love a dystopian sci-fi, Fortress was likely very flat on paper. Enhancing the generic outline—which revolves around Christopher Lambert’s ex-Special Forces soldier being sent to a high-tech underground prison—is the inventive visuals. Director Stuart Gordon brings some of his singular taste for body horror, startling to see in an otherwise by-the-numbers action movie. Fortress does a good job in its first half of delivering Lambert in a desperate and impossible situation, and though the action sequences down the stretch aren’t absolutely top drawer, its energetic pace and the originality of the design makes it extremely fun. Then there’s Kurtwood Smith as the warden, revelling in his villainy as only Kurtwood Smith can, every contour on his unusual shaped head shot in extreme close up, captured on celluloid forevermore.

23. Bad Day for the Cut (Chris Baugh, 2017)

Why don’t Ireland make more genre movies? Cast in the mould of a classic revenge tale, Bad Day For the Cut follows a quiet farmer as he slays his way through the Belfast criminal underworld to avenge his mother’s murder. It’s a wildly satisfying watch as leading man Nigel O'Neill battles local hoods like an Irish Charles Bronson. My only complaint is that it could have gone further and been more bloody, more violent, and straight up meaner.

22. Road House (Rowdy Herrington, 1989)

Road House is pure grown up fantasy. I refuse to believe there is a corner of America that resembles this movie—even Jasper, Missouri. There can’t be a place where large scale bar brawls break out with impractical regularity. Hell, there can’t be a place that have bars like the joints in Road House, with blues rock bands live every night and bouncers who look like Patrick Swayze. I hope such a world doesn’t exist anyway. Who wants to go to a town where all the men put on dead jeans after work to get rowdy and disrespectful? In the fantastically entertaining Road House, they’re all just tomato cans for Swayze to knock over. In the end, the fantasy of this movie isn’t just the world, it’s that we all kind of want to be more like Patrick Swayze.

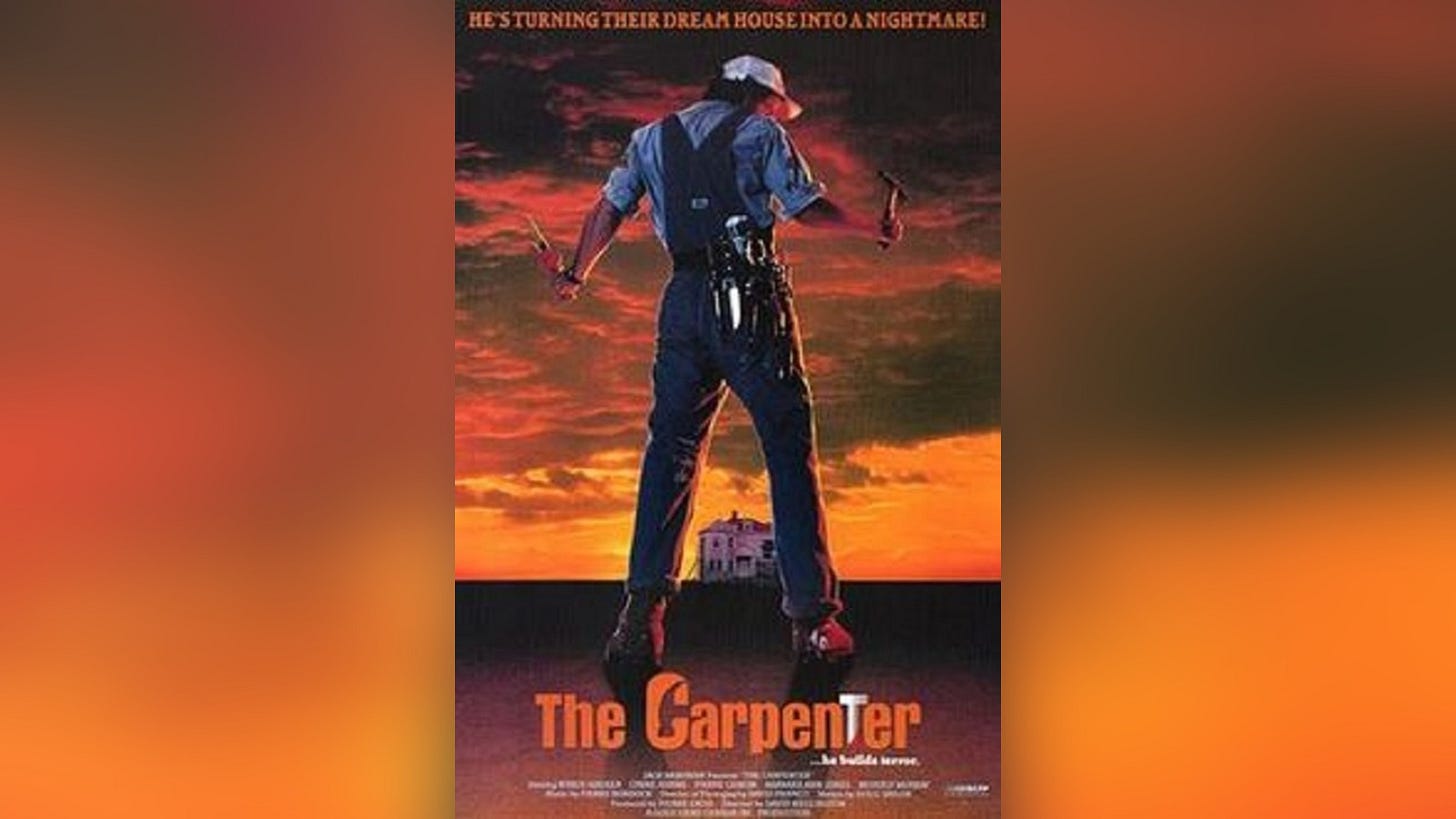

21. The Carpenter (David Wellington, 1988)

The Carpenter is an intriguing and gripping little slasher flick about a woman (Alice Jarett) recovering from a mental breakdown and the charming carpenter (Wings Hauser) who serves as a kind of guardian angel to her. A more low key piece than your average #BeyondFriday movie, the violence is startling when it does come. What makes the movie, though, is the chemistry between the leads is excellent—Jarett’s ghostly visage reflecting a vulnerability that makes the affable carpenter all the more enchanting.

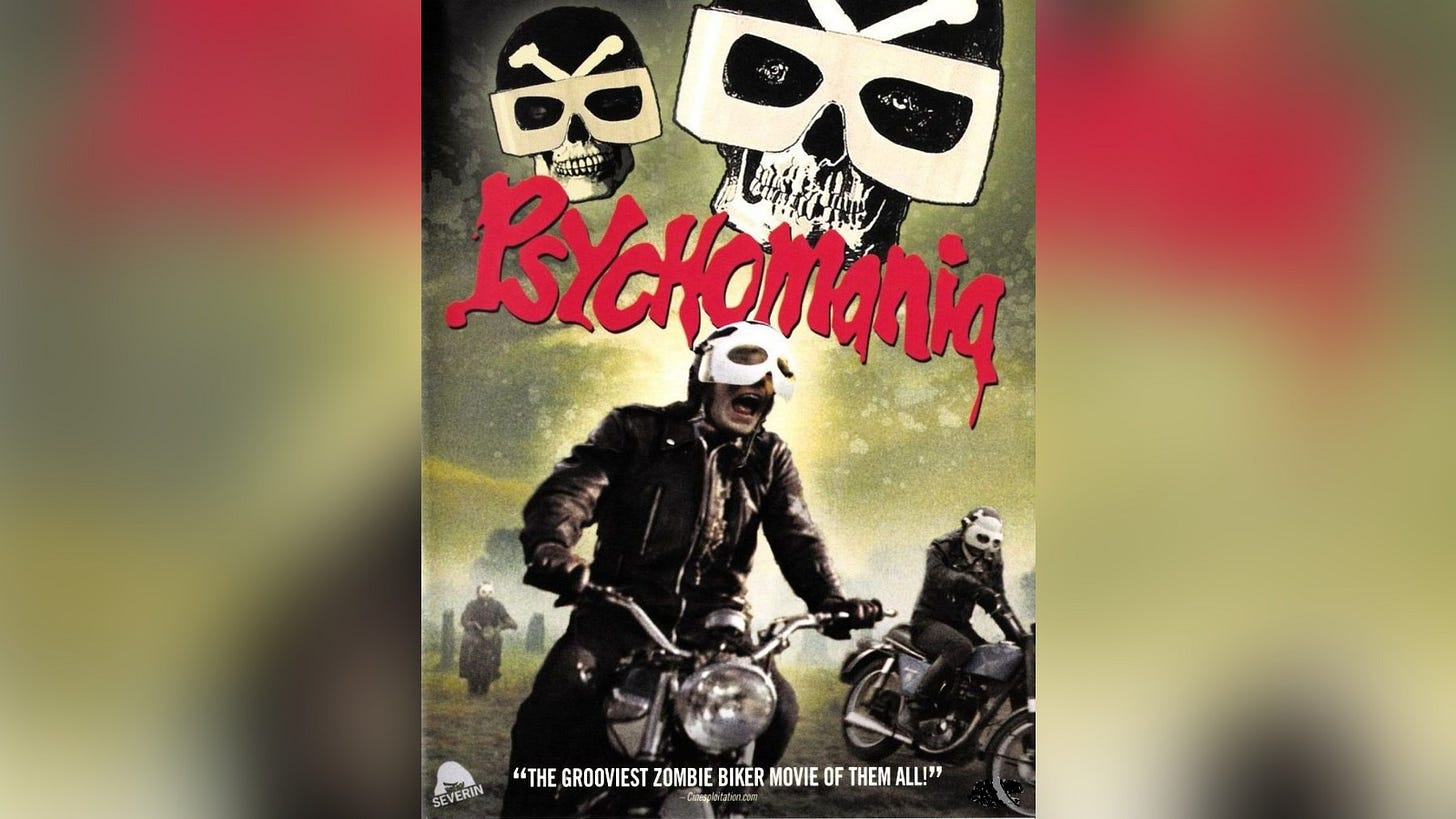

20. Psychomania (Don Sharp, 1973)

Psychomania captures the ritualistic nature of biker culture. From the outside, these customs and formalities can feel like they stretch back centuries when you know they can’t have existed longer than a couple of generations. The movie opens with British biker gang The Living Dead circling some monolithic stones on their bikes and, from there, director Don Sharp fits the contrasting imagery together like pieces in a puzzle. Then there’s the depiction of the British aristocracy, a dying cult of its own in the 1970s, which juxtaposes the anti-social menace of The Living Dead. Mix in elements of the occult and you’ve got some tarry cinema. The movie sometimes veers into the ridiculous—most bizarrely, the gang decide to bury leader Tom as he sits vertically on his motorbike, fully clothed, petrol in the tank, simply to set up the moment where, resurrected, he accelerates up from the dirt. For the most part, though, it’s on the right side of the line.

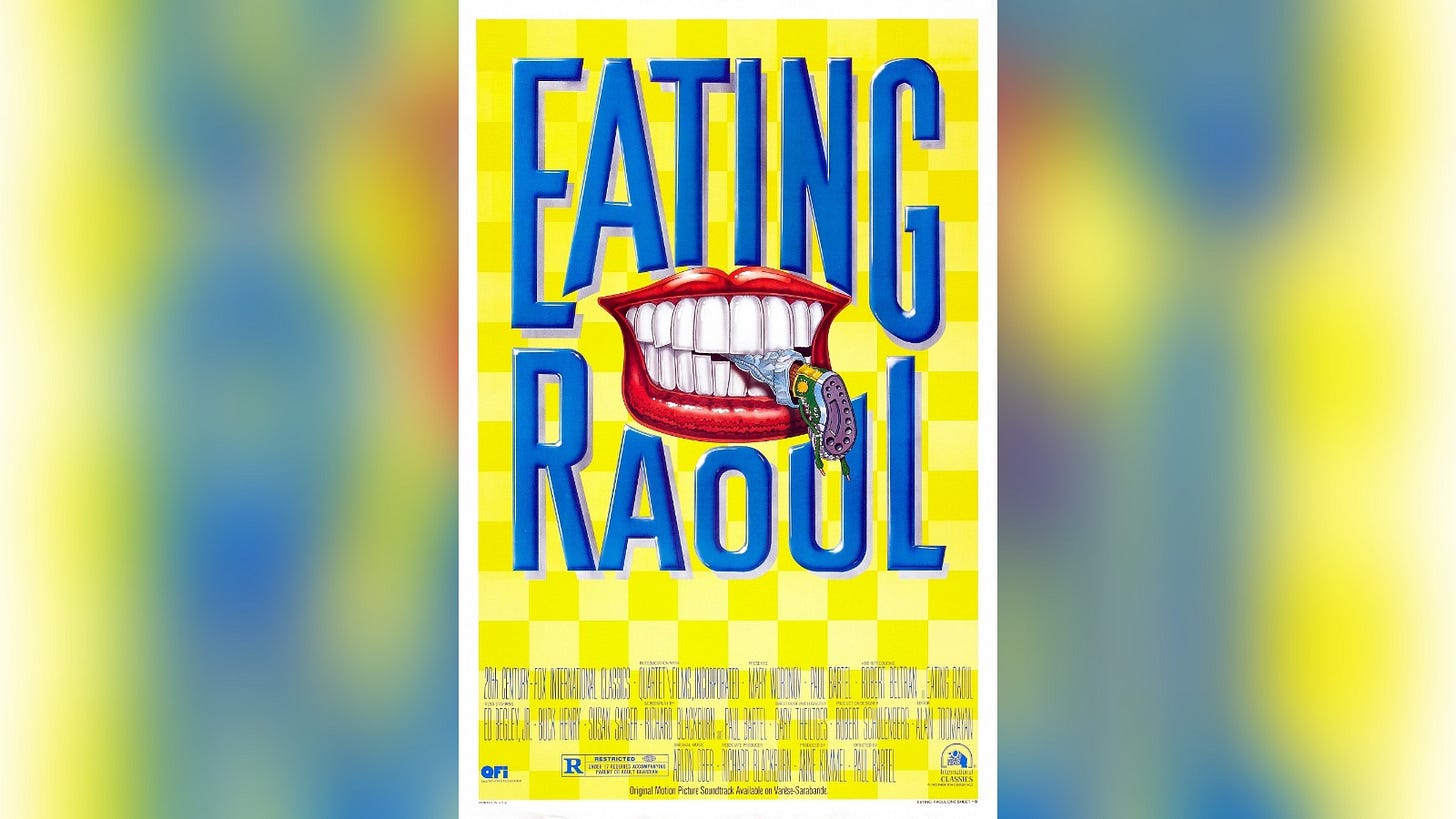

19. Eating Raoul (Paul Bartel, 1982)

Swinging was a sensation in the early 1980s and cocaine wasn’t feared. Living adjacent to this hedonistic world are married couple the Blands, a vision of puritanical America who sleep in separate single beds like Basil and Cybil Fawlty. Financially stretched, the Blands stumble on a scheme. Wife Mary (the exceptional Mary Woronov) poses as a specialist sex worker, husband Paul (Paul Bartel, also the director) murders them for their money, and petty criminal Raoul (Robert Beltran) disposes of the bodies. Eating Raoul is about the battle between the chaste and the liberated at the heart of many societies, the key battleground being Mary’s spirit as she becomes tempted by an affair. Yes, this is a comedy—darker than the darkest comedy was ever dark, with ugly sexual violence and slapstick farce holding hands throughout. The perversions that Mary’s clients dream up are particularly riotous—in one scene a man dresses in full Nazi uniform to play the role of her sadistic captor. Even when the laughter comes, director Bartel never allows you to stop squirming.

18. Passenger 57 (Kevin Hooks, 1992)

Wesley Snipes has made all kinds of movies throughout his brilliant career but Passenger 57 made him an action star. Passenger 57 is in the great tradition of movies that tried to replicate the Die Hard formula in different settings (I’m also fond of Under Siege, which is Die Hard on a boat, and Under Siege 2, which is Die Hard on a train). Here, Snipes plays a security consultant dragged into a terrorist plot to hijack an airplane. It’s a solid outline and Wesley finds an acceptable amount of ass to kick. If anything, Passenger 57 could have been 10 minutes or so longer—not as much of the movie takes place on the plane itself as you might expect.

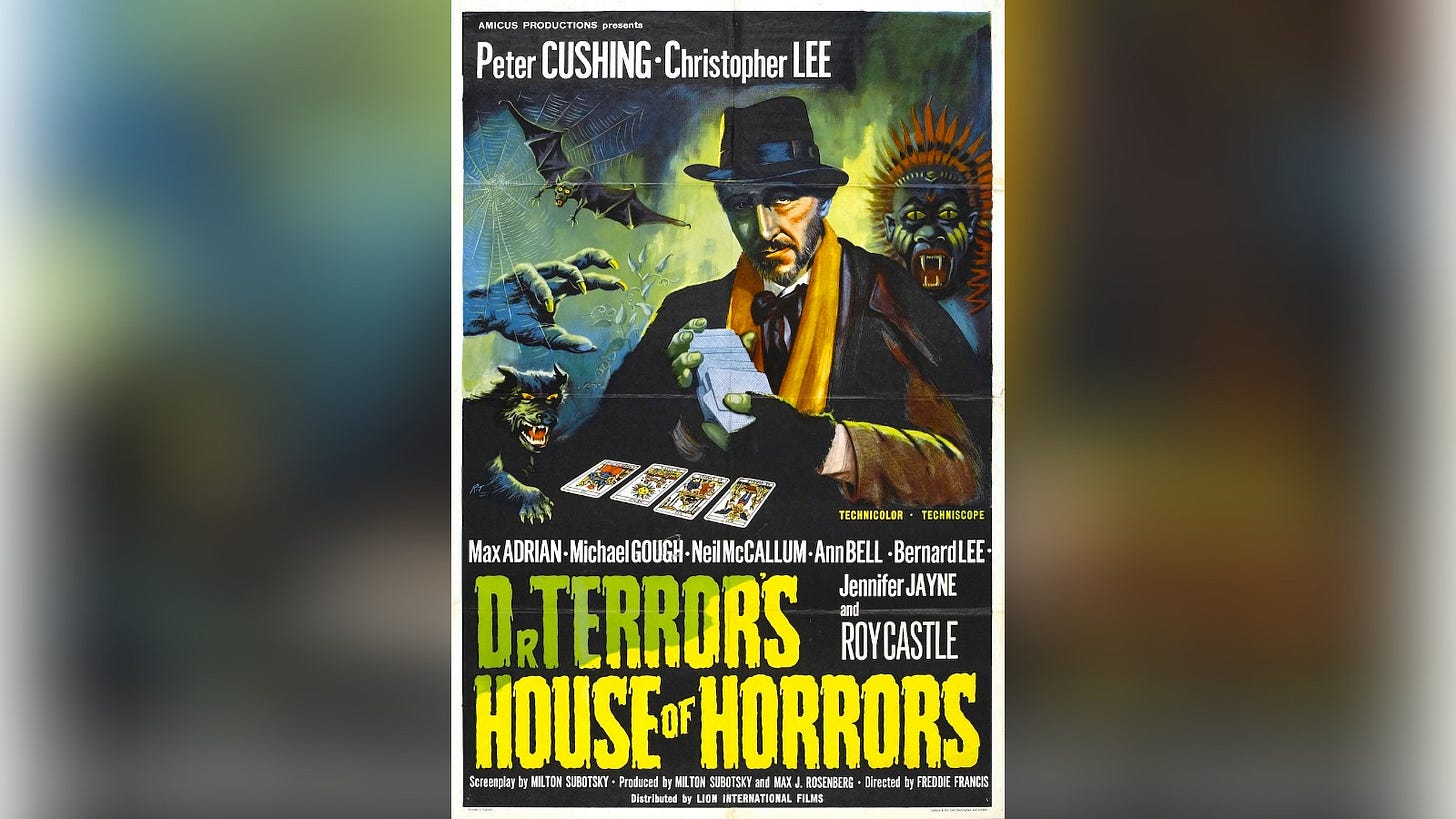

17. Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (Freddie Francis, 1965)

I was completely unaware of British anthology horrors as a genre before Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors. The film, directed by Freddie Francis, is essentially a series of shorts, tied together by a wicked premise: Five men in a train carriage are individually told of their destinies by the Tarot card-reading Doctor Schreck (Peter Cushing). There’s vampires, werewolves, voodoo, and killer plants in these fortunes. But my favourite segment features Christopher Lee as the pompous art critic, haunted by a disembodied hand. It’s fantastic to see horror tropes done with flair before they got played out.

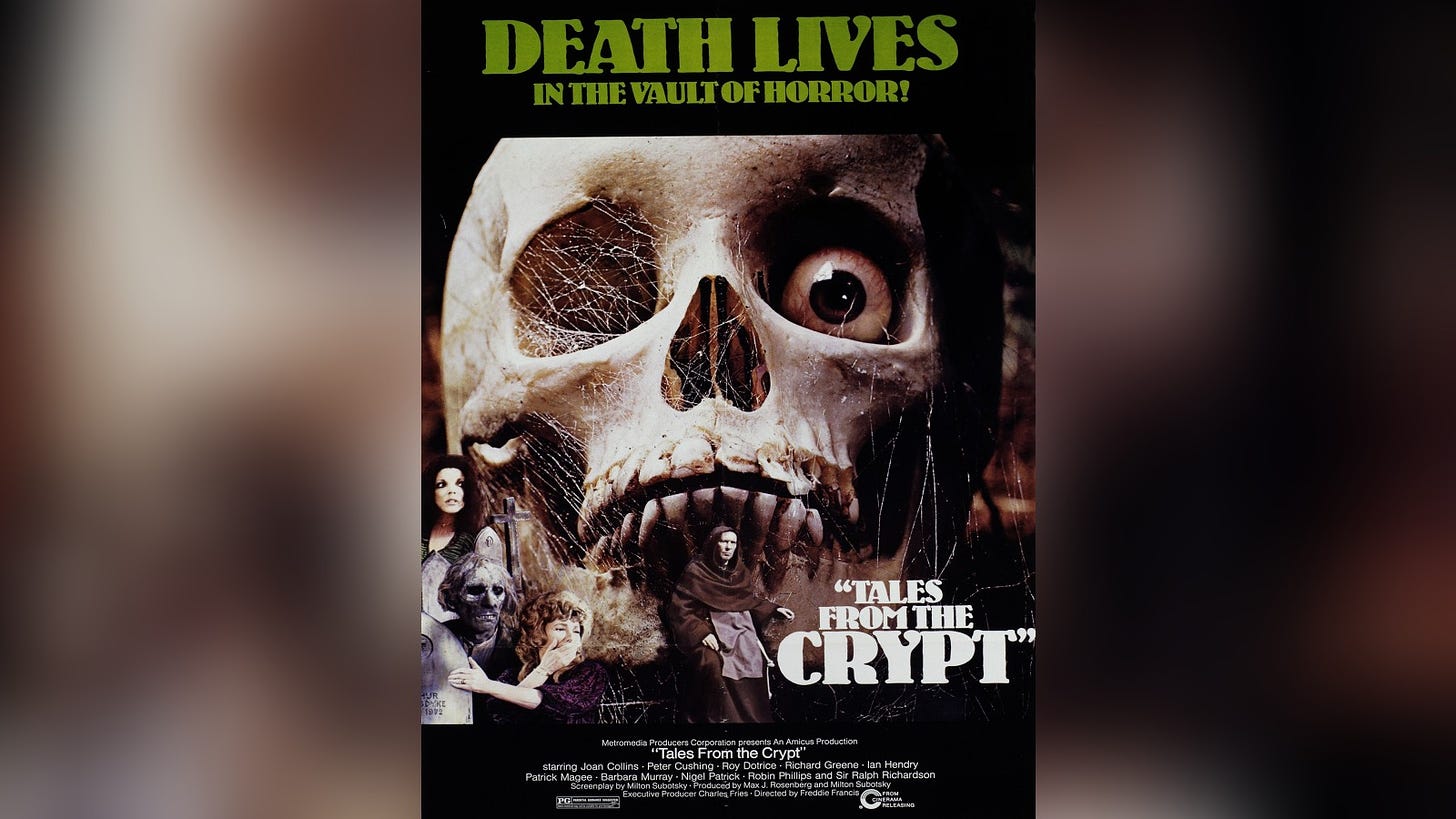

16. Tales From the Crypt (Freddie Francis, 1972)

I really didn’t have a choice but to place both Freddie Francis anthology horrors back to back. They’re very difficult to separate. I’ve given the edge to Tales from the Crypt for two tales in particular: its chilling reimagining of the monkey’s paw and story of an evil home for the blind manager who gets his comeuppance. Though just as entertaining as Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (which was seven years old at this point), Tales from the Crypt pushes boundaries that bit further.

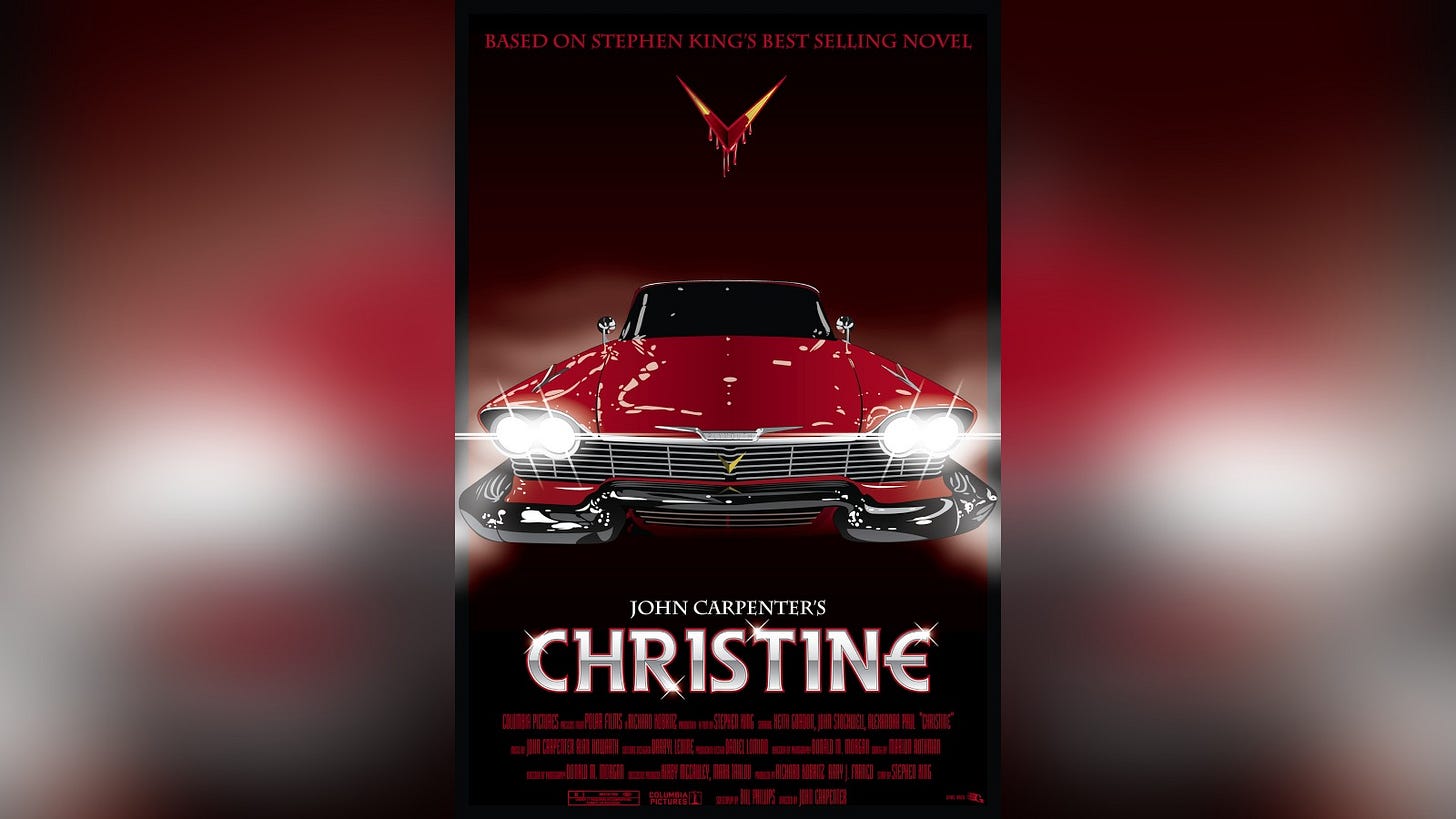

15. Christine (John Carpenter, 1983)

There’s two things that define 1950s American pop culture. The first is the teenager—the myth of the American teen starts in the ‘50s. The second is muscle cars. Frequently, the two collide. What John Carpenter, working from a story by Stephen King, does with Christine is subvert both mythologies to corrupt the image of American innocence. What better time to do this than the 1980s, the decade of excess, Reagonomics, and crack. Through his sentient 1958 Plymouth Fury that he names Christine—a perfect vision of American freedom—the awkward and unpopular ‘80s kid transforms into a ‘50s greaser to enact revenge on all bullies and enemies, contaminating the mythology of post-war prosperity, Christine’s impossibly red paint shining brightly in the pitch black night time backdrops.

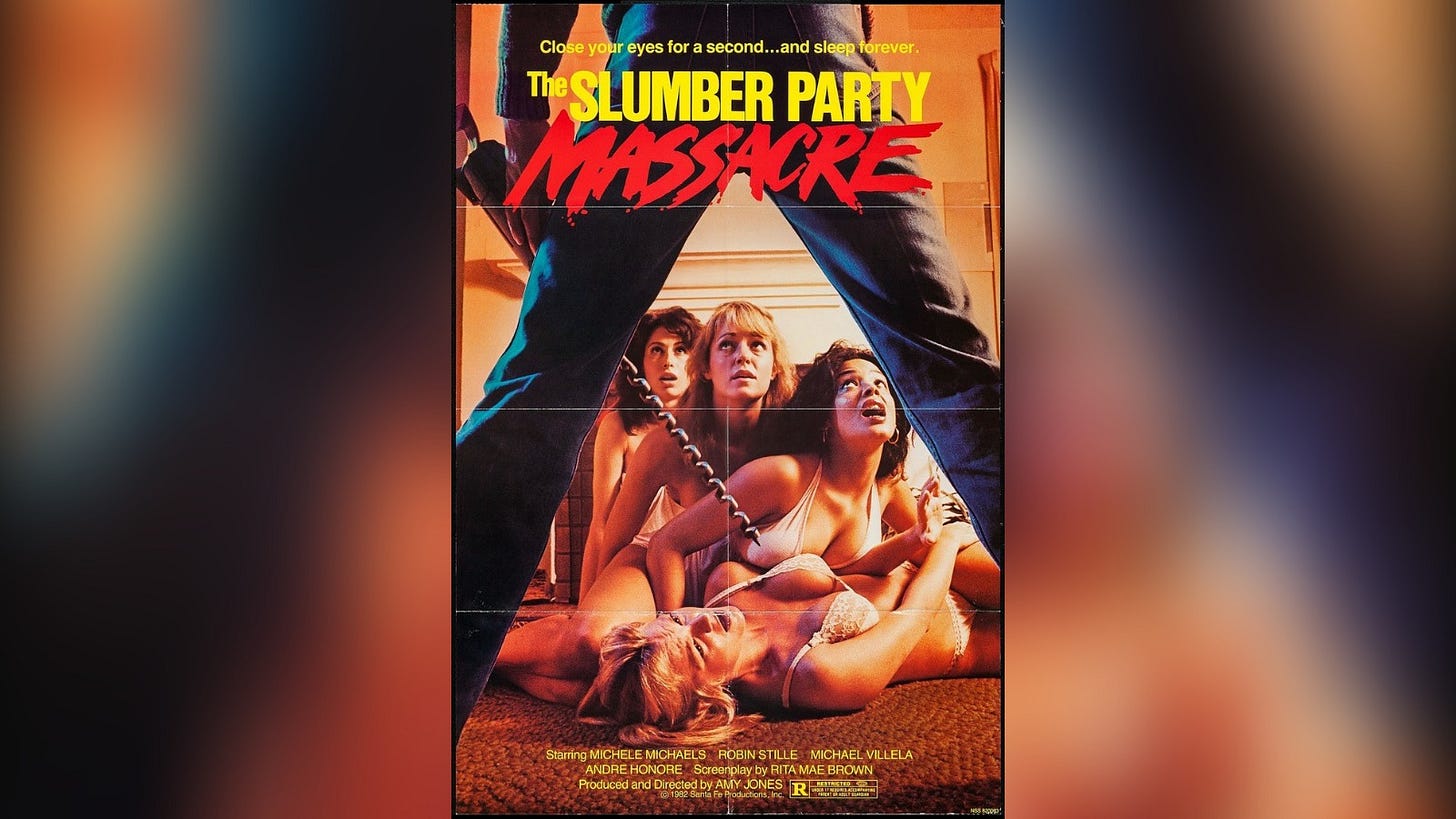

14. The Slumber Party Massacre (Amy Holden Jones, 1982)

The Slumber Party Massacre pops cliches like they’re TicTacs. This movie never met a violent horror cliche it didn’t like. They’re the kind of cliches that Scream would play with years later. Don’t creep around the shadows of the house alone. If you’re a teenager in a slasher flick, don’t even think about having sex or you will be punished. Though familiar, The Slumber Party Massacre does everything with a grissly verve. The movie wisely reveals its killer early on so there’s no mystery here. His motivations are barely investigated. All that matters is the hunt. And when a heroine emerges from the pack of poor teens and springs into action with her selected weapon, it’s a moment that should exist as permanent horror movie iconography.

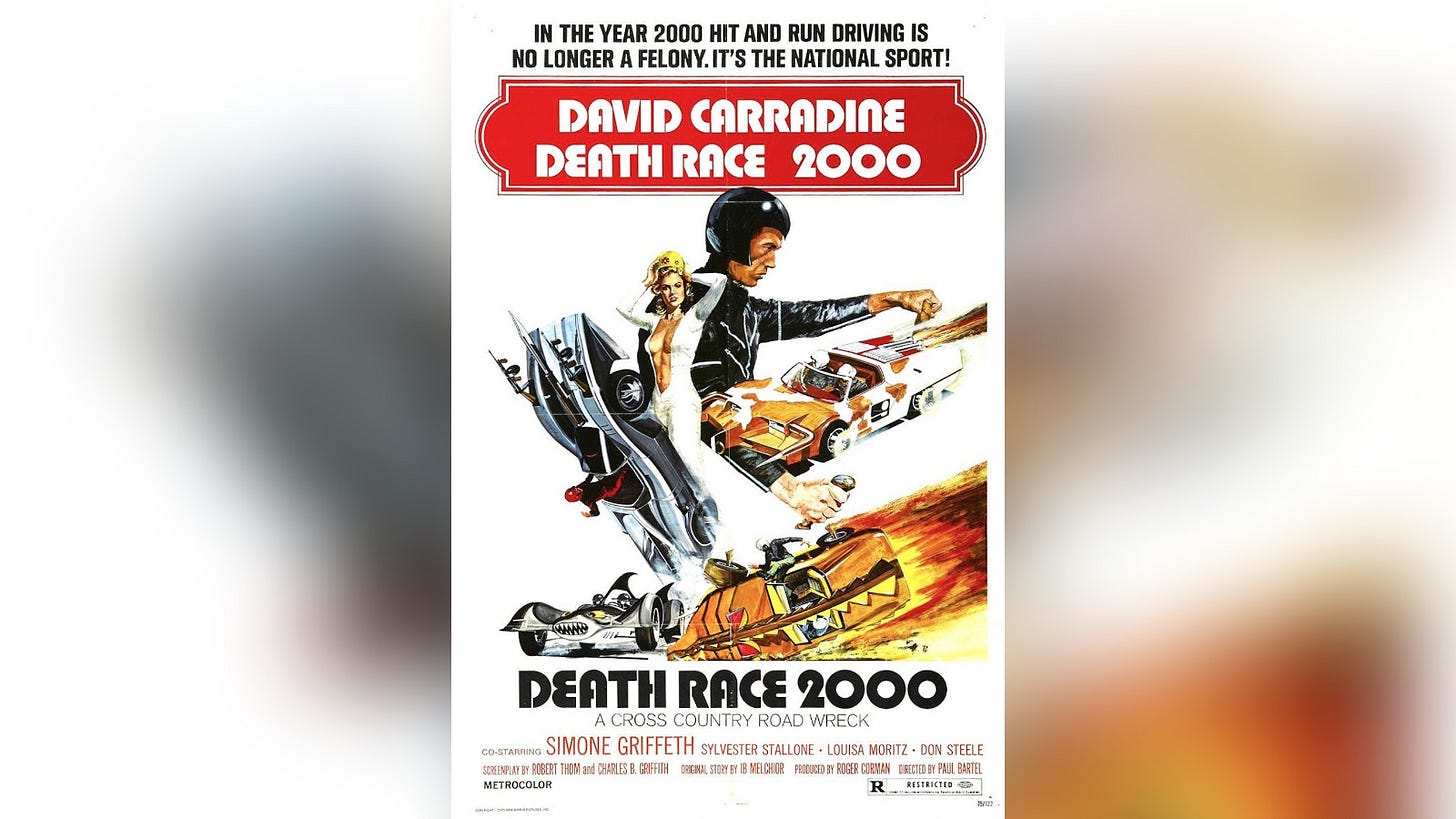

13. Death Race 2000 (Paul Bartel, 1975)

Death Race 2000 is in the great tradition of movies set in a future where brutal forms of entertainment organised to pacify the population. See also: Rollerball, The Running Man, and Gamer. Unlike those dystopian visions, director Paul Bartel envisions this murderous road race as a kind of grown up Wacky Races, featuring characters with fantastic personas and plenty of crazy moments—take the scene when hospital staff roll out some stricken patients for their hero Frankenstein to mow down only for the driver to swerve into the staff themselves. It’s easy to imagine a more traditional action star in the role, but David Carradine plays the haunted Frankenstein, said to be part-human and part-machine, with steely determination. (The remake, which retained little of the original bar the death racing, starred Jason Statham and is also very good). Carradine is complimented by a supporting cast that includes Mary Woronov and a young Sylvester Stallone, who all enjoy themselves. It’s difficult to find any modern day allegories in the shallow social satire, but who cares? Death Race 2000 is campy fun that zips along like Frankenstein’s alligator motor.

12. Over the Top (Menahem Golan, 1987)

Over the Top was released in an era when Sylvester Stallone was watchable in absolutely everything he graced, so I’m very surprised I’d never heard of this little arm-wrestling movie. It’s half road movie, half 1980s sports drama—the final third is cast from the same mould as The Karate Kid and Bloodsport—and all music video as director Menahem Golan, with the help of the great Giorgio Moroder, includes crazy amounts of ‘80s hard rock songs (the kind that grunge soon destroyed), lyrics and all. Over The Top embraces its silliness, and so it should. And still Stallone’s attempts to win over his estranged son are surprisingly touching. It’s unfortunate it was panned upon release—the bad bastards even gave the kid in it two Golden Raspberrys for fuck sake.

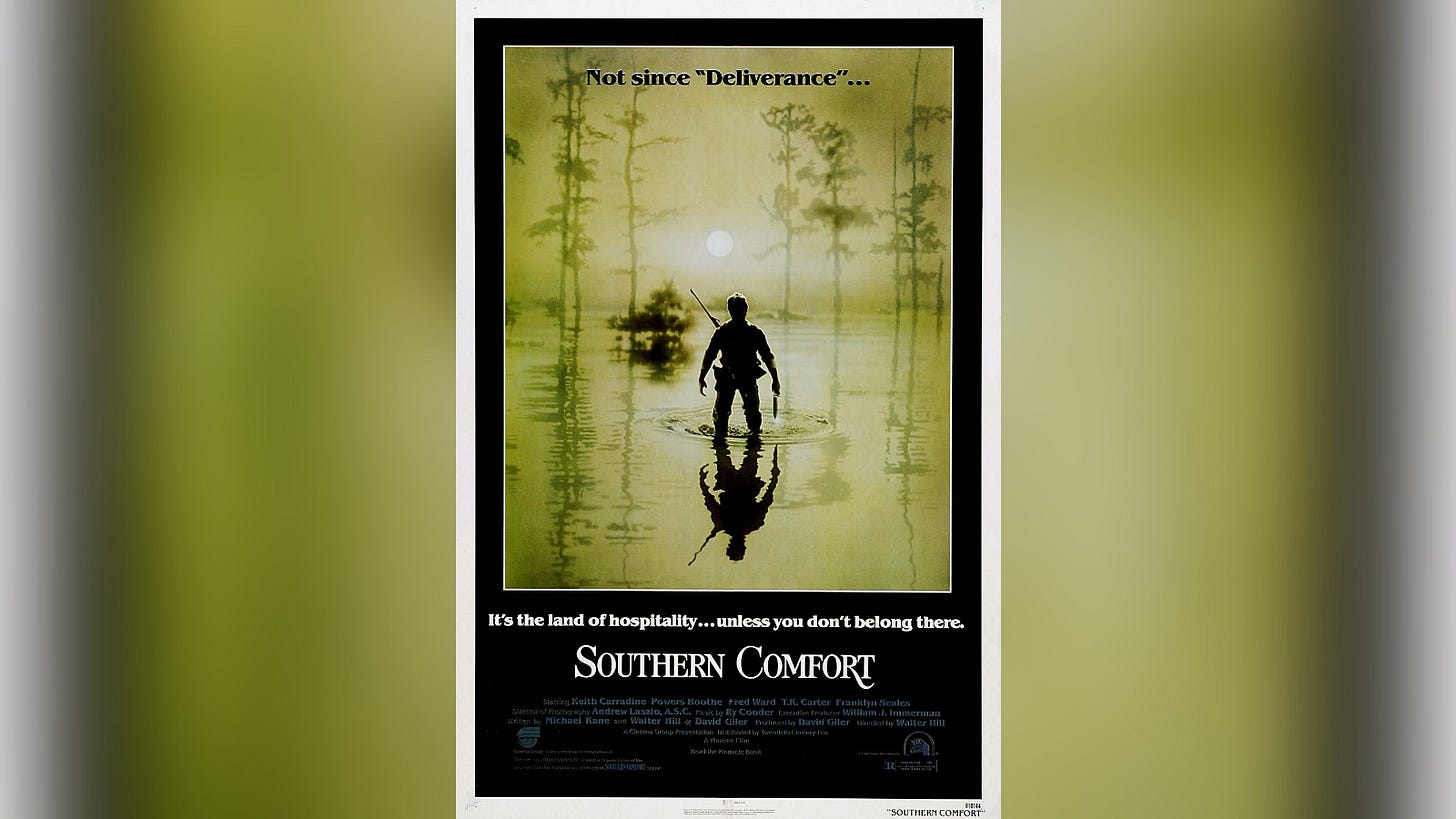

11. Southern Comfort (Walter Hill, 1981)

The central message of Southern Comfort couldn’t be clearer: soldiers who mess with the local population deserve everything coming to them. “It real simple,” says one Cajun when asked why Hell has been unloaded on a squad of Louisiana National Guardsmen who come trouncing through their bayou as part of a training exercise. “We live back in here. This is our home, and nobody don't fuck with us.” Louisiana is a not too subtle allegory for Vietnam here (though Ry Cooder’s swampy guitar never lets you forget where you are), and Southern Comfort attempts to crack into some classic war movie themes: that is, that the hearts of men are easily corrupted and capable of great evil when dropped into combat. The platoon, led by Keith Carradine and Powers Boothe, and uniformly excellent, with every moment of fear, anger, and paranoia seeping through the screen.

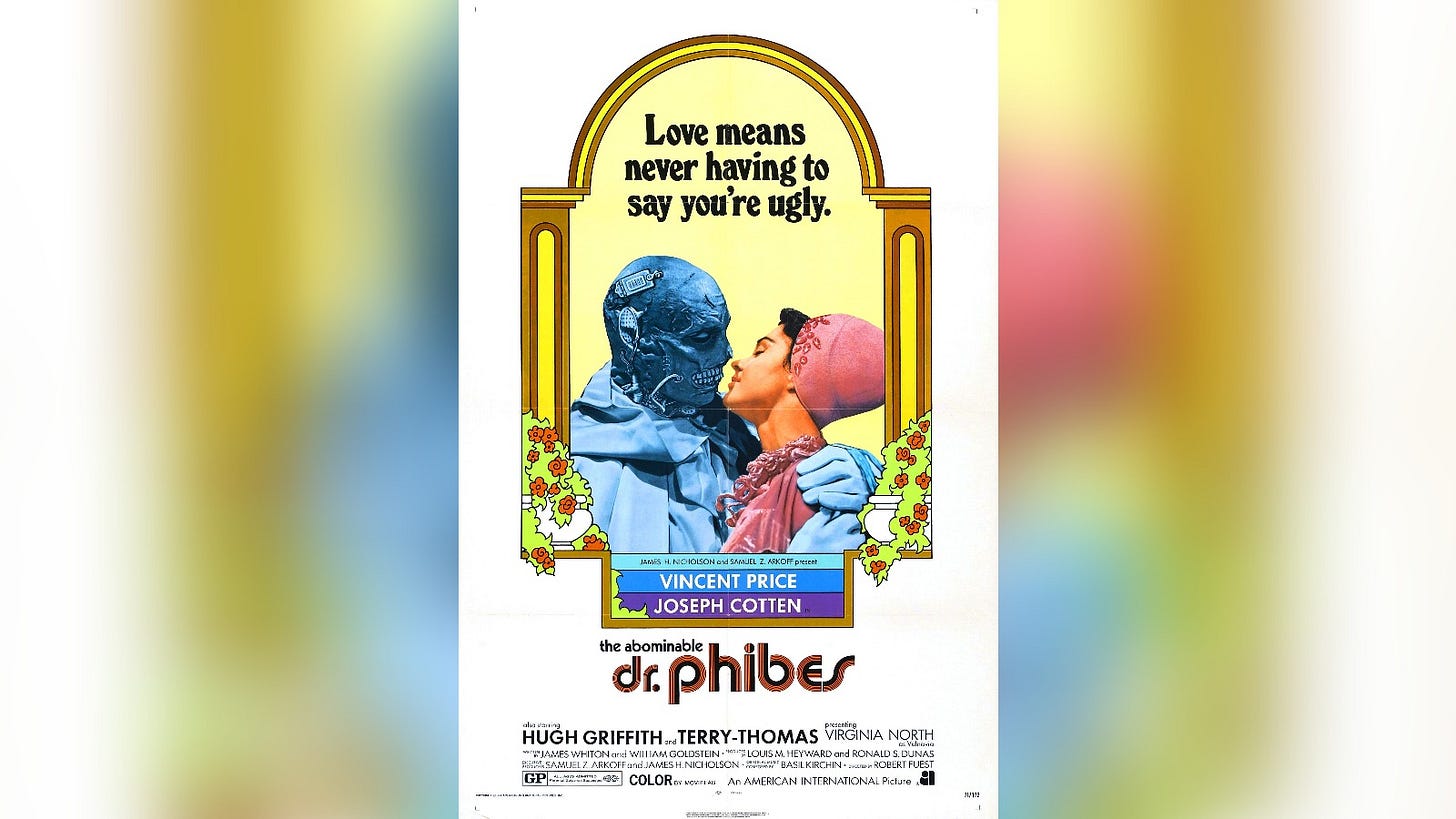

10. The Abominable Dr. Phibes (Robert Fuest, 1971)

Malevolency, thy name is Vincent Price. The Abominable Dr. Phibes has an excellent premise: the bad doctor blames the medical team that attended to his wife's surgery for her death and takes influence from the Ten Plagues of Egypt from the Old Testament when exacting his vengeance on each one. Elevating that embryonic idea is the creepy set design, the wicked humour, the presence of an aging Joseph Cotton, and, of course, Price, ashy faced, with a Paul Simon haircut, hamming it up in a way that demands full attention.

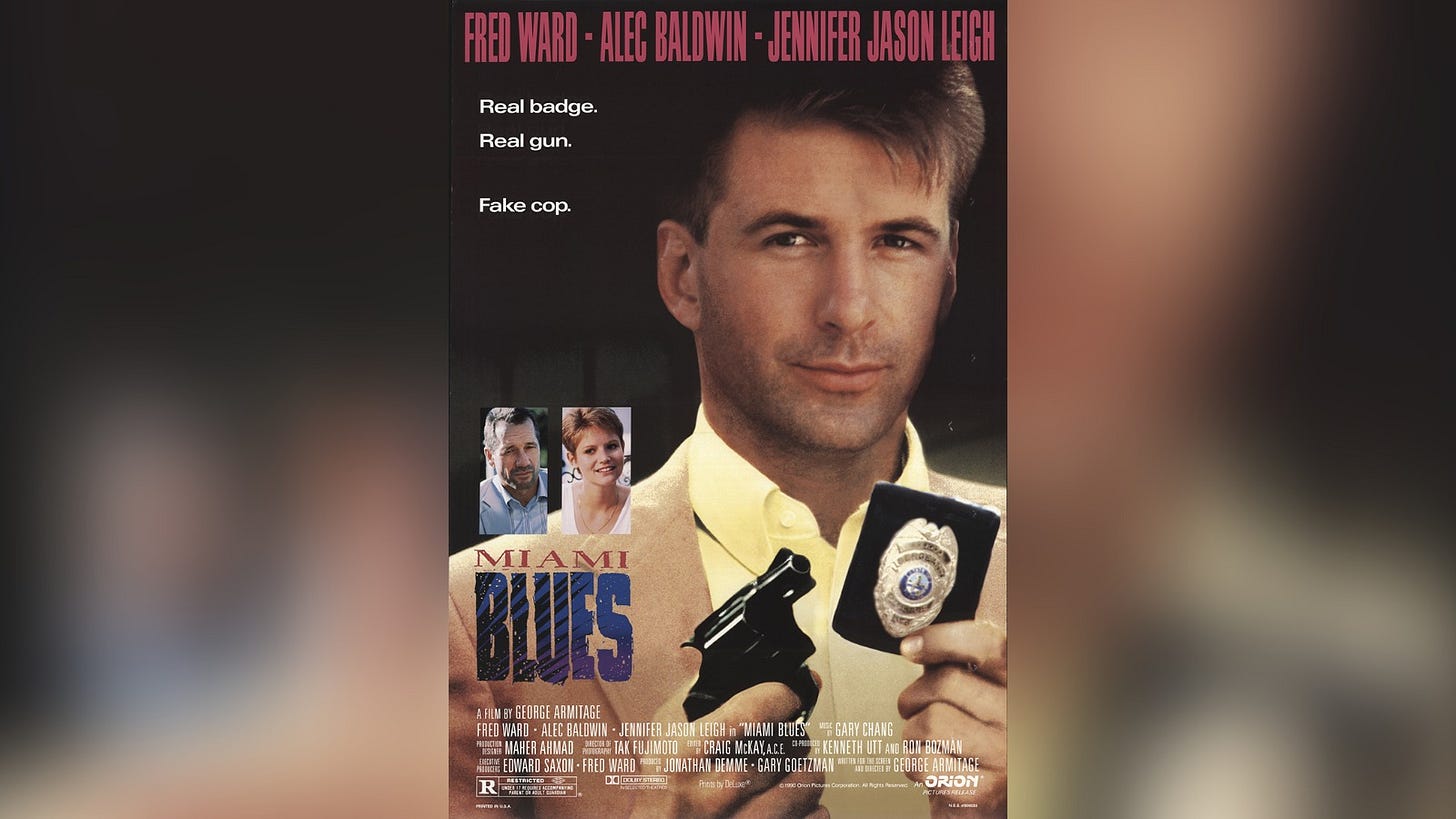

09. Miami Blues (George Armitage, 1990)

Every time I see young Alec Baldwin in a movie I wonder why he gave up actual acting to be a... I dunno, celebrity figure? There was so much potential there that post-The Cooler has been wasted in bit parts, cameos, and a whole bunch of other appearances he should have said no to. And I felt this way even before I copped Miami Blues, which has got to be Baldwin’s definitive vehicle. A snappy crime caper, he plays fresh-out-of-jail convict Junior who journeys to Florida to start a new life. Damn though, Junior almost immediately murders a Hare Krishna (albeit somewhat accidentally) before engaging in a petty crime spree by posing as the detective on his tail, played by the relentless Fred Ward. Meanwhile, Junior tries to hold together a relationship with a sex worker Susie (Jennifer Jason Leigh), who despite her new beau being rough around the edges, comes to represent her chance at an idyllic life. Leigh is so effective in the role that as I watched the movie, I almost cared about nothing but her character’s happiness, even as the electric Baldwin was threatening to leap off the screen. Then there’s the city of Miami. There’s only a small amount of blues music in Miami Blues but there’s a lot of Miami and those famous boulevards are essentially a character. Though released in 1990, the movie fits comfortably in the ‘80s run of when Miami was America’s true pop culture capital.

08. The Hitcher (Robert Harmon, 1986)

Of all the #BeyondFriday movies, The Hitcher feels most like an obvious selection of what the high council of movie selectors is trying to achieve. This menacing and grisly piece work has permanent residency in the cult movie canon. The plot is wickedly simple: a psychopath stalks a young motorist as they traverse the barren landscapes of deep Texas, the image of the open American road so often associated with freedom—Springsteen and all that—presented here as a void impossible to escape from. The Hitcher could broadly be described as a slasher movie, but while most slasher movies hide their killers in the shadows until the second half, director Robert Harmon gets you right up close with Rutger Hauer’s John Ryder from the off. You can almost taste the sweat off his brow. And yet Ryder and his motivations remains a total mystery. For some, this is a weakness in the film. I disagree. The meaninglessness of his unstoppable harassment of protagonist Jim Halsey (C. Thomas Howell) makes him all the more unnerving.

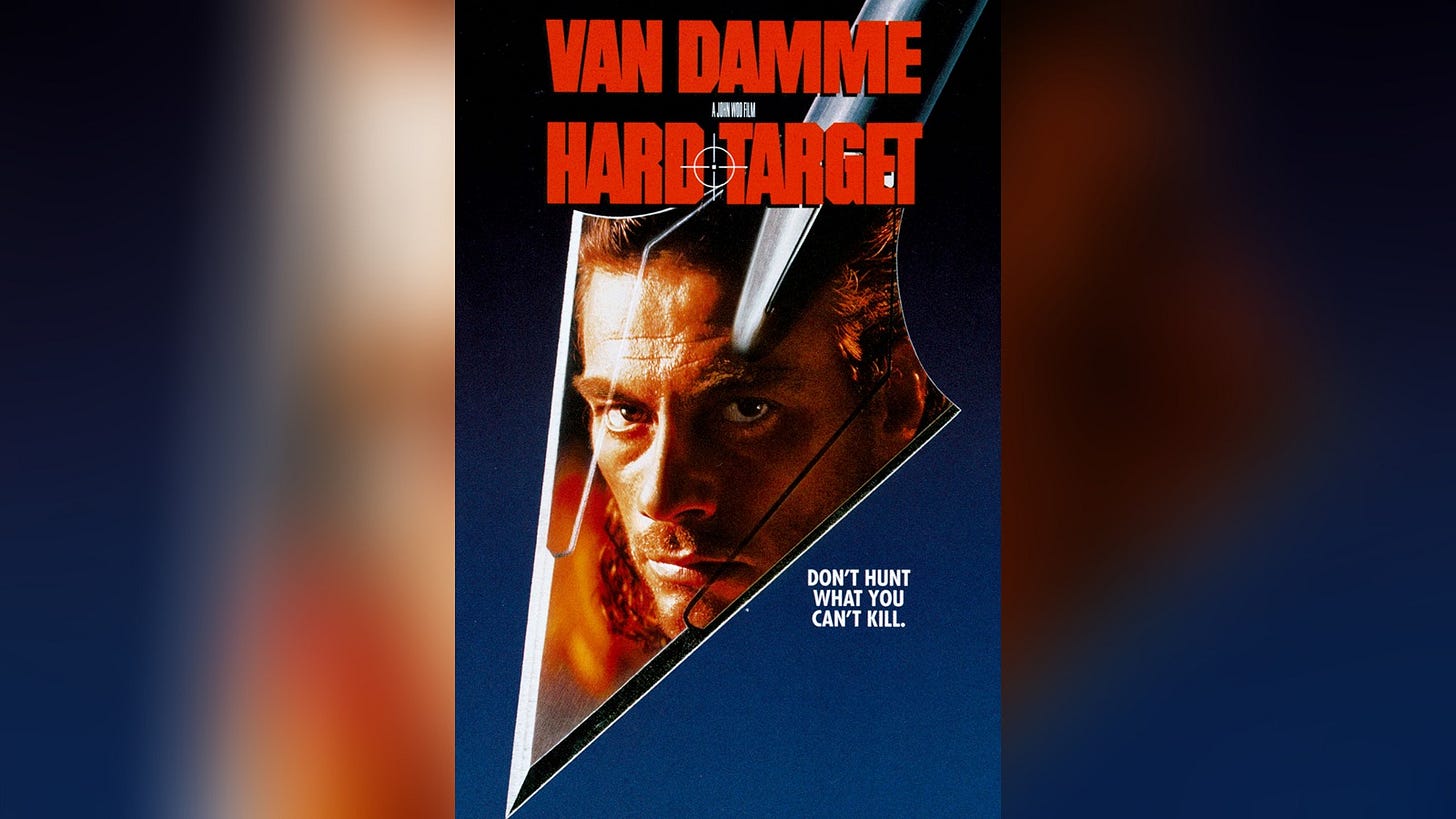

07. Hard Target (John Woo, 1993)

I am obviously a massive fan of John Woo’s mid-1980s to early ‘90s Hong Kong work. Those movies have a permanent place in the canon of action movie classics. Underrated, though, is Woo’s initial Hollywood run: Hard Target, Broken Arrow, and Face/Off. It helped Woo that he could kickstart his American adventure with Jean-Claude Van Damme. I’m not sure why Van Damme has yet to be given the credit of some of his action star contemporaries. Maybe it’s because in recent years he’s so often played a pastiche of his persona that only works if you believe his movies are terrible. Or it could be that he never made a film that netted film crit acceptance to act as a critical fulcrum to his body of work. Whatever the case, the year before Hard Target, Van Damme made Universal Soldier, and the following year he made Time Cop. Needless to say, this was his absolute peak, and the action in Hard Target is absolutely crazy. Though it took until Face/Off for Woo to put all his trademark touches into a Hollywood movie, the finale of Hard Target features some of those operatic rhythms to his shoot outs that makes him without peer. And by the way, Van Damme made good movies for longer than you think. Check out Universal Soldier: Regeneration, from 2009, and thank me later.

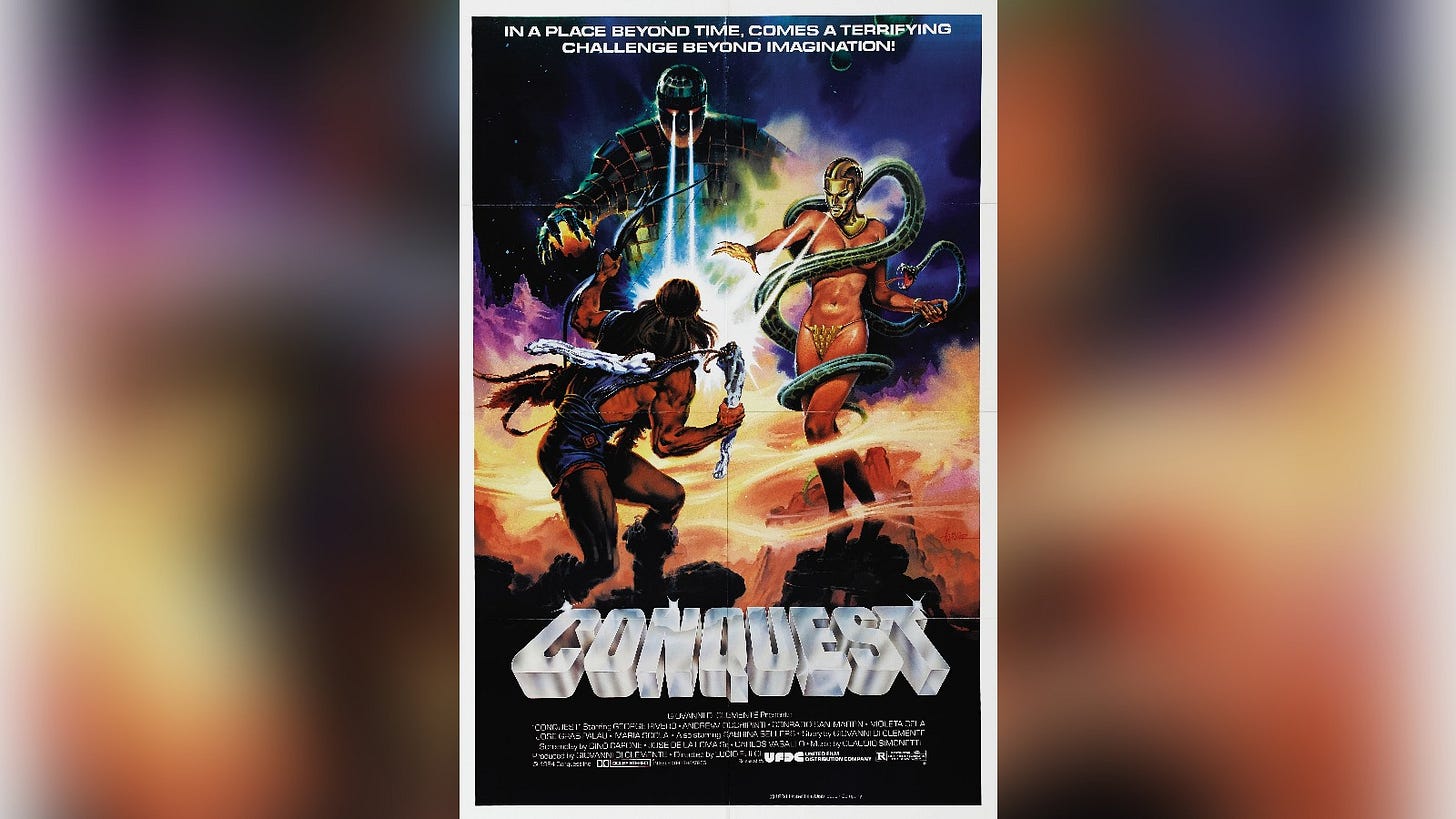

06. Conquest (Lucio Fulci, 1983)

Conquest is the kind of movie you throw on towards the end of a session for all the bugged-out beatniks still hanging around your living room—the kind of movie that when those blurry-eyed viewers wake up, they question whether this crazy thing they’d witnessed was actually some mad hallucination. A Golden Axe-style high fantasy, Conquest follows young warrior Ilias, who leaves his people to embark on a rites of passage journey into a strange, barren land. Pursued by a sorceress who suffers visions of being slayed by him, Ilias links up with nomadic warrior Mace, from which point the plot can be summarised by Mace’s assertion that the pair will simply journey “wherever our feet carry us.” Legendary horror director Lucio Fulci offers no explanations or apologies for this fantasy world, where wookie-esque creatures feed on human brains and flesh, where water zombies surface, where dolphins are a man’s best friend, where a battle-hardened outlaw like Mace can look a bit like Fabio. The whole movie is the proverbial banquet for the eyes and ears. Yet I found the harshness of the world to be strangely moving. Fulci’s universe feels so vast, so bleak. You can walk anywhere but nowhere. Feels strangely apt for these times.

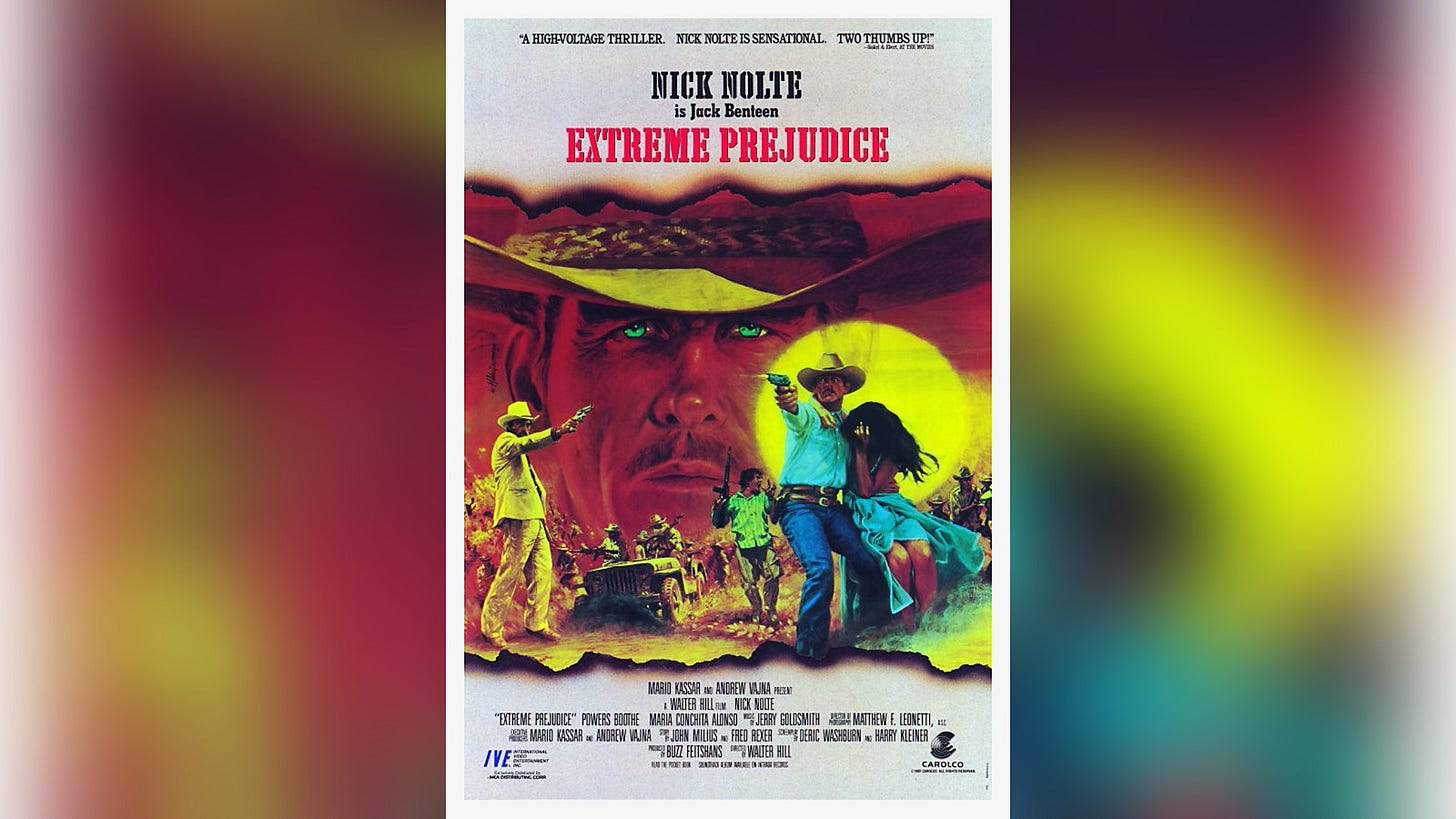

05. Extreme Prejudice (Walter Hill, 1987)

Extreme Prejudice is a hardboiled little contemporary western with six loaded chambers of ambition. It’s a face off between two old friends cast on both sides of the law—Nick Nolte’s tough as nails Texas Ranger and Powers Boothe’s intense drug trafficker, with a love interest played by María Conchita Alonso caught in the middle. But it’s also about a unit of officially dead soldiers in Texas on a secret mission. It’s easy to envision most productions insisting the script was sheared of some of its elements. Extreme Prejudice goes another direction—absolutely loading the cast with amazing actors and flooding the movie with action set pieces. The great Michael Ironside leads the army unit which includes William Forsythe. Rip Torn plays a sheriff. At the centre of it all, Nick Nolte. I love Nick Nolte. A proper old school movie star who took on a wide variety of roles, I like him best in these grizzled-as-an-old-shoe roles. And, of course, Boothe, who spent his career acting a bastard and making it an art form. With its blood-splattered shoot outs, dusty sets, and rebellious anti-hero, Extreme Prejudice is a classic of the neo western genre.

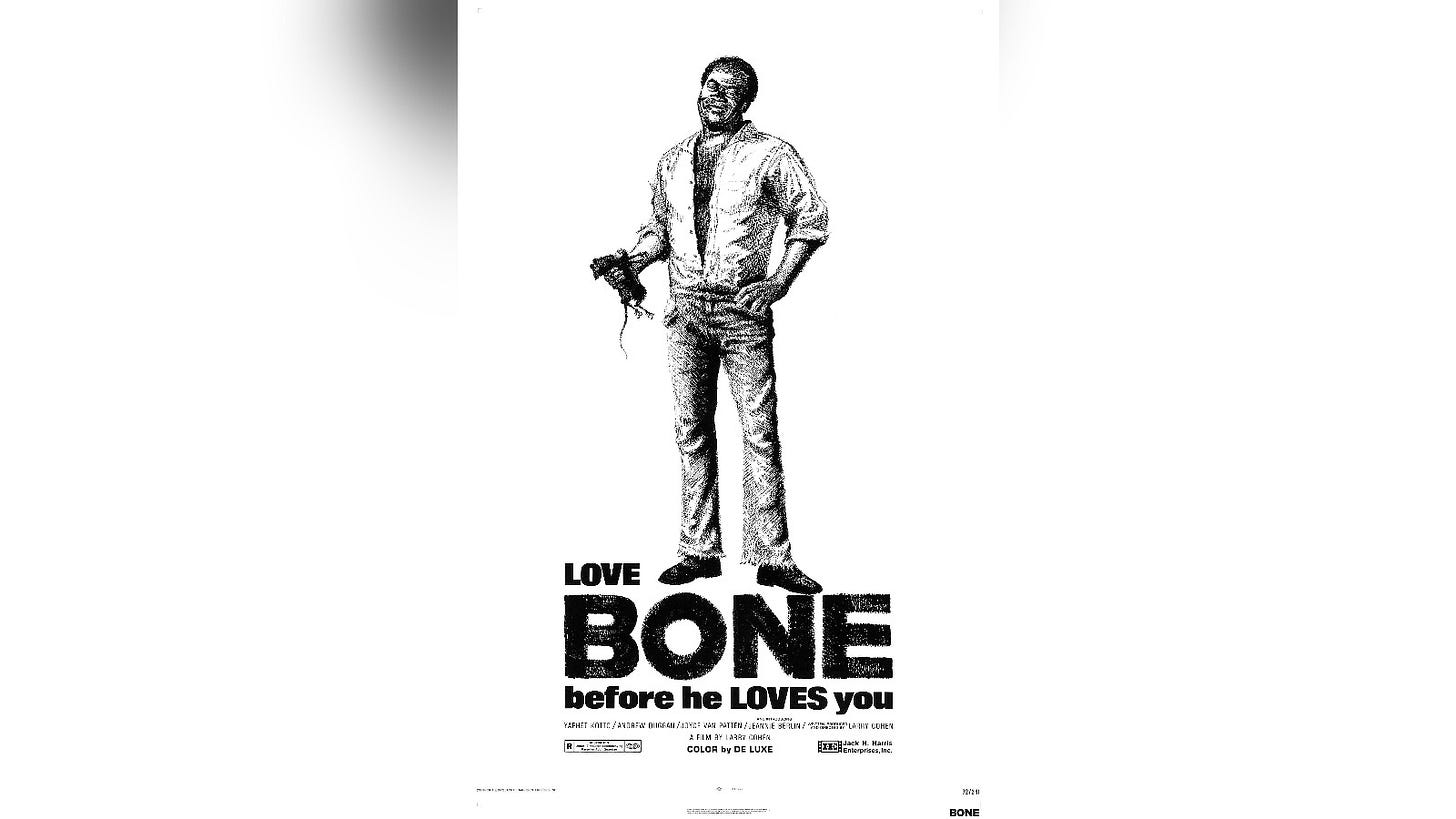

04. Bone (Larry Cohen, 1972)

Here I was expecting a straight exploitation flick. Instead, Bone is one of the sharpest commentaries on race and class, poverty and wealth, and America of its era. It’s directed by Larry Cohen (if you haven’t noticed already, he’s the most prominent creative of #BeyondFriday) and helps to confirm something I’ve long suspected: that filmmakers capable of making movies like The Stuff actually have more to say on these topics than Hollywood’s big ticket directors. How Bone must have rattled 1970s American audiences. The movie follows the title character (Yaphet Kotto), a wandering criminal, as he enters a Beverly Hills home of an affluent couple, sending husband Bill (Andrew Duggan) to the bank to fetch a ransom while he stays with wife Bernadette (Joyce Van Patten). The tension from minute one is almost unbearable. Cohen invites white America to examine its racial prejudices. Bone himself is determined to play the role of dangerous Black criminal, but he cannot, begging the question of whether he felt boxed into the perception by a racist society and his own desperate situation. The movie’s depiction of how white women weaponise their whiteness predicted countless viral clips 50 years later. Back then, you probably could have told a lot about a person by who they perceive as the heroes and villains of Bone. The biggest villain here is the country that set different parameters for people based on their race.

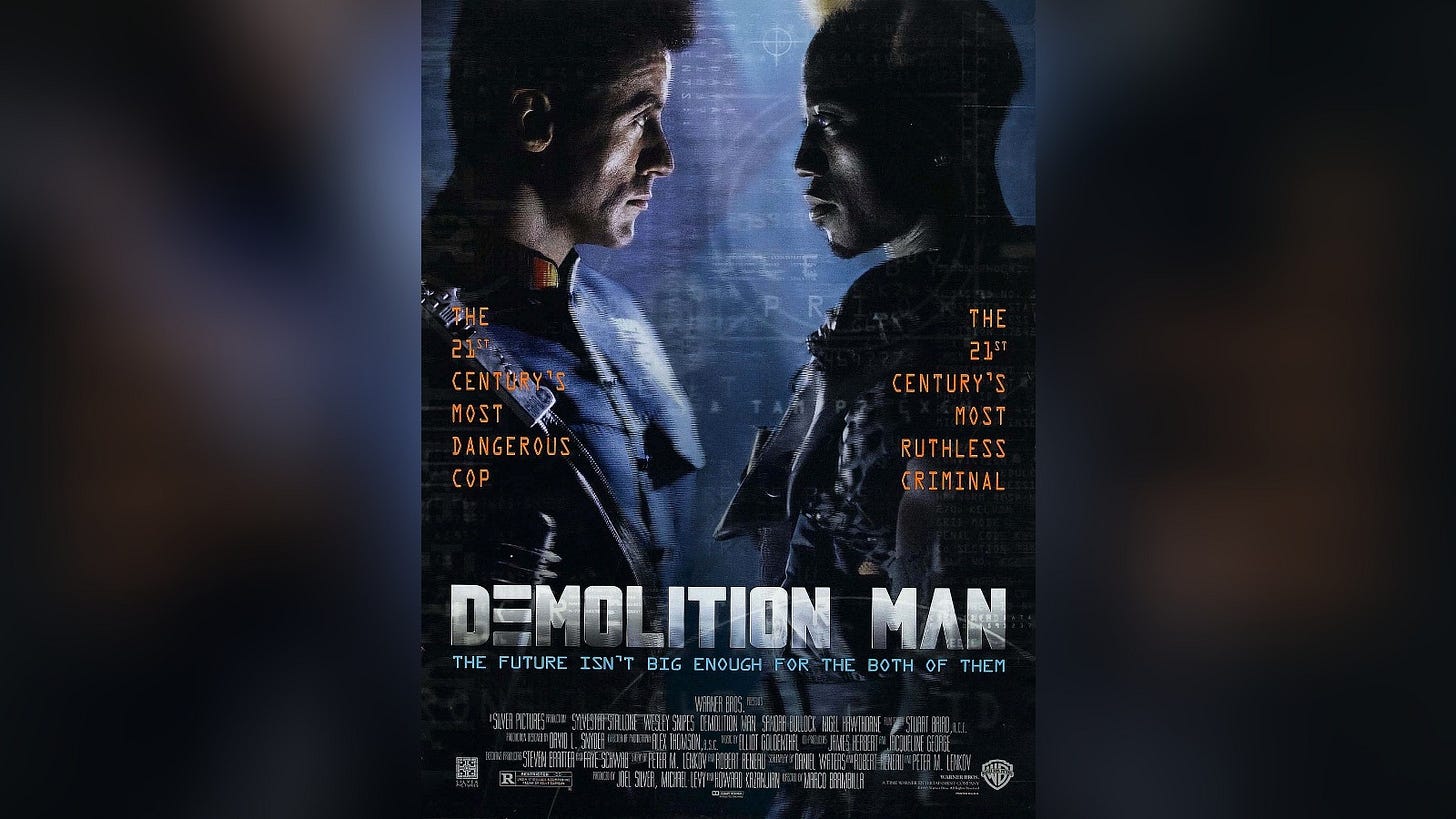

03. Demolition Man (Marco Brambilla, 1993)

I remember so clearly watching Demolition Man for the first time when I was a kid. It was simple channel surfing that brought me to the scene that sees Wesley Snipes—a fantastic vision with his bleach blond hair and dungarees—use kung fu to wipe out an entire squad of cops. I, of course, had to watch the whole thing. Simply put, was one of the most entertaining movies I’d ever seen and continues to be so some 25 years later. You can quibble about its logic holes and other flaws, but when you hit the big red play button, Demolition Man just works, every time.

Futuristic action movies tend to set in the thick smog of a dystopian hell. Demolition Man invites you to consider whether there’s something worse than that: a faux-utopian nanny state. There’s a magic to the way the movie drops two muscle bound SOBs from a chaotic past—Snipes’ Simon Phoenix and Sylvester Stallone’s John Spartan—into a future world of no crime and perfect manners is executed to perfection. Sandra Bullock and Benjamin Bratt’s sunny disposition sells the universe; Snipes goes so far over the top as the almost Looney Toons-giddy psychopath, almost every single line is a quotable (and I do quote them all the time). Then there is Stallone. So rarely has Sly been given the chance to emulate his great rival Schwarzenegger’s more humorous brand of action performance. Here, he finds the appropriate light touch as the only sane person in a huge asylum, using his character’s disbelief at what the future has become to sell gag after gag. Marco Brambilla fuses together all his elements into a perfect piece of popcorn entertainment. Maybe it’s all he had to give to Hollywood. Brambilla hasn’t made another major movie before or since.

02. Total Recall (Paul Verhoeven, 1990)

Total Recall seems an unusual choice for a #BeyondFriday movie—it was, after all, the fifth highest grossing movie of 1990 and has hardly fallen from memory in the three decades since its release. If that success surprises you, it’s perhaps indicative that modern Hollywood takes fewer risks nowadays. With the industry content to let the money-printing franchises mop up all the resources and talent, it’s impossible to imagine a violent and trashy bodyshock sci-fi like Total Recall being allowed to succeed now. For me, #BeyondFriday counterbalances (or perhaps accentuates) my frustrations with modern mainstream filmmaking, and so Total Recall is actually an ideal pick.

The movie is a perfect marriage of the three hands that guided it. Though Philip K. Dick’s original short story We Can Remember It for You Wholesale offered only a starting point, Total Recall retains the writer’s fascination with alternate realities and authoritarian regimes, which dovetails with director Paul Verhoeven’s inherent distrust of both private enterprise and media saturation. (It is via both the 24-hour news cycle depicting upheaval on Mars an advertising bombardment of the company Recall that pushes hero Douglas Quaid into the action.) Then there is Arnold Schwarzenegger, the perfect embodiment of the kind of angular human being that fascinates Verhoeven. This was Arnie at the peak of his powers, all smirk and one-liners, uncontainable on any screen, his inherent ridiculousness offering a sense of levity as he runs around Mars, knee-deep in a rebellion, trying to figure out the nature of what is and is not real. The star’s light performance afforded Verhoeven some slack to build his vision of Mars in earnest—see how the director insists rebellion leader Quato, a misshapen creature growing out of a man’s stomach, is presented with great dignity. Lots of movies before and since have invited viewers to question the nature of reality long after the curtain drops—including the Arnie-starring knock off The Sixth Day and a lifeless remake starring Colin Farrell—but Total Recall was so impactful, it’s cast a shadow over everyone who has investigated the same theme.

01. Zombie Flesh Eaters (Lucio Fulci, 1979)

One of the many, many alternate titles Zombie Flesh Eaters was released under was Zombi 2, as producers tried to pass it off as a sequel to Dawn of The Dead. This is obviously extremely cheeky, but I will say this about the movie: it’s the greatest zombie film I’ve seen not to feature the input of George A. Romero. That man Lucio Fulci crams Zombie Flesh Eaters with so much dynamic imagery, the movie glides from iconic moment to iconic moment, flooding your senses with unabashed pulp carnage, never letting you settle for a second. These elements can be quiet—how Fulci captures disheveled Dr. David Menard’s ritual of wrapping zombie victims in clean white sheets before firing a bullet into their heads as they slowly rise depicts man’s determination to maintain the dignity of the dead that is present in the best zombie films. And highlights are, of course, overt too: see how a single zombie terrorising the Doctor’s wife in her home uses classic creeping, tension-filled horror filmmaking before a memorable death. The zombies here are proper shuffling terrors, reflecting Romero’s original image of decaying reanimated corpses, too stricken to move quickly, their danger mostly coming by mass numbers and relentlessness.

Then there’s the shark versus zombie underwater battle. This is obviously a great idea, executed here in a real “how did they do it” fashion. It’s as if Fulci had a briefcase worth of zombie ideas stored in his twisted mind and wanted to make sure absolutely none went to waste. Nothing will ever top Dawn of the Dead’s satirical punch, moving character development, and invitation to consider what you’d do in the same situation. But Fulci did something very different: made a zombie horror that kicks all kinds of ass, one where you want to shout “fuck yeah!” at the screen every few minutes. I don’t know if Zombie Flesh Eaters is the best #BeyondFriday movie, but nothing encapsulates the blood-splattered, dirty dirty, video nasty, buck-fuckin’-wild nature of the late night movie club than this.

This is a free post for all my #BeyondFriday comrades and B-movie brethren. If you’d like to support what I do here, please consider subscribing.